AIRBORNE MAGAZINE NR.16

Uitgave van de Vereniging Vrienden van het Airborne Museum

Airborne Magazine is een uitgave van de Vereniging Vrienden van het Airborne Museum Oosterbeek en verschijnt drie keer per jaar. Het doel van de VVAM is bekendheid geven aan het Airborne Museum, de activiteiten van de Vereniging Vrienden en aan de geschiedenis van de slag om Arnhem.

Redactie: Alexander Heusschen (magazine@vriendenairbornemuseum.nl), Jasper Oorthuys, Otto van Wiggen

Bijdragen van: Wybo Boersma, Bernhard Deeterink, Alexander Heusschen, Bob Hilton, Erik Jellema, Leo van Midden, Martijn Reinders, Natalie Rosenberg, Hans Timmerman, Otto van Wiggen

Vormgeving: Sandra van der Laan-Elzinga, Studio 223, Elst

Druk: Grafi Advies, Zwolle

Contactgegevens VVAM: www.vriendenairbornemuseum.nl info@vriendenairbornemseum.nl (06) 510 824 03

Postadres: Wissenkerkepad 22 6845 BW Arnhem

Archivering & losse nummers: info@vriendenairbornemuseum.nl

INHOUDSOPGAVE

3 Museumnieuws – Verbouwing Airborne Museum Hartenstein

4 Verenigingsnieuws – Agenda ALV 2020 / lezing ‘The Lost Company’

5 Mededelingen – Veranderingen in 2020

6 Conflictarcheologie – Duits hoofdkwartier in Villa Heselbergh

12 Thema – 1st Airborne Reconnaissance Squadron

22 Ministory 132 – 3rd Parachute Battalion op de Falklands en in Arnhem

29 Bits and pieces – De Royal Enfield 125- motor van het Airborne Museum

32 Achtergrond – Verborgen Market Garden-schatten van Erfgoedcentrum Rozet

35 Programma

Omslag: Maandag 18 september 1944

Lance-Sergeant William ‘Bill’ Bentall in een jeep van ‘D’ Troop, 1st Airborne Reconnaissance Squadron, met de Nederlandse burgers H. Piek en B. Versteegh, aan het westelijke einde van de Backerstraat in Oosterbeek (copyright foto: D. van Woerkom)

BIJDRAGEN

De redactie van Airborne Magazine hoort graag uw reacties en suggesties. We verwelkomen bijdragen aan het blad. Vraag voor een soepele verwerking van uw artikel en/of beelden naar de auteurshandleiding via magazine@vriendenairbornemuseum.nl.

VERBOUWINGSPERIODE AIRBORNE MUSEUM HARTENSTEIN VAN START COLLECTIE

V.l.n.r. Sarah Heijse (directeur-bestuurder museum), burgemeester Agnes Schaap, Jory Brentjens (con-servator).

Bij het uitruimen van de collectie hielpen onder ande-re Gido Hordijk, Bart Bijl en Jessica Zoutendijk-van de Sman. In 2009 richtten Gido en Bart de vitrines op alle verdiepingen volledig in, nu ging de collectie opnieuw door hun handen om het veilig op te bergen voor de verbouwing.

COMPLETE VERNIEUWING

De vaste presentatie op de eerste verdieping wordt compleet vernieuwd. De vitrines en panelen zijn ver-wijderd om plaats te maken voor de nieuwe inrichting.

Hetzelfde geldt voor de tijdelijke tentoonstelling Het Netwerk die plaats maakt voor de kindertentoonstell-ling Waterschapsheuvel. De Airborne Experience krijgt een indringender karakter. De ondergrondse ruimte wordt opgeknapt en uitgebreid. Er komen drie nieu-we scènes bij die de bezoekers nog meer betrekken in de operatie van september 1944. Wybo Boersma heeft geadviseerd bij de uitwerking van de verhaallijn op de eerste verdieping en de daarbij behorende collectie-stukken. Oud vitrinemateriaal is aan Museum Huis-sen gegeven en de Paasbergschool heeft het meubilair van de educatieve ruimte gekregen. Gepoogd wordt om zo min mogelijk weg te gooien en zoveel mogelijk items te schenken aan goede doelen. Zo is het decor van de tentoonstelling Het Netwerk geschonken aan het Platform Militaire Historie Ede.

MEERTALIGE AUDIOTOUR

Ook zal er een meertalige audiotour (nl, en, du) wor-den ontwikkeld waaraan de vooraanstaande historici Sir Antony Beevor, Dr. Matthias Strohn en Ad van Liempt gaan meewerken. Zij gaan 60 unieke collec-tiestukken voorzien van extra context en een persoon-lijke verhaal. Ook komt er een speciale audiotour voor kinderen.

NIEUW BEZOEKERSRECORD

Veel mensen kwamen in de laatste weken voor de slui-ting naar het museum om de tentoonstelling Het Net-werk nog te kunnen zien. Dit zorgde ervoor dat het museum in de maand oktober heel goed werd bezocht, net als in de voorgaande maanden. In tien maanden tijd kwamen maar liefst 105.058 mensen naar het Air-borne Museum, een nieuw bezoekersrecord!

HEROPENING

In maart 2020, ruim voor de herdenking van 75 jaar vrijheid, wordt het Airborne Museum heropent.

Benieuwd naar de voortgang van de verbouwing?

Op www.airbornemuseum.nl/verbouwing vind je de laatste updates.

– Natalie Rosenberg

Sinds 28 oktober is het museum gesloten voor een grootschalige verbouwing. Burgemees-ter Agnes Schaap was bij de start van de voorbereidende werkzaamheden om de collectie veilig op te bergen.

V.l.n.r. Jessica Zoutendijk-van de Sman, Bart Bijl, Gido Hordijk, Jelle Hofs.

VERENIGINGSNIEUWS

Omdat de volgende editie van Airborne Magazine pas in april 2020 verschijnt, informeren wij u nu alvast over de algemene ledenvergadering (ALV) die op zaterdag 21 maart 2020 plaatsvindt. U ontvangt geen uitnodigingsbrief meer per post; dit bespaart de vereniging een hoop kosten. We hebben dit keer gekozen voor congrescentrum Lebret, Lebretweg 51 in Oosterbeek. De start van de vergadering is om 10.30u. De zaal is geopend vanaf 10.00u.

Aanmelden voor de ALV kan via activiteiten@vriende-nairbornemuseum.nl. Geeft u aan welke dagdelen u bij-woont: ochtend, middag of beide.

De vergaderstukken zullen aan het begin van de vergade-ring klaarliggen bij de ingang van de zaal. U kunt de stuk-ken ook downloaden in het afgeschermde ledendeel van de verenigingswebsite (www.vriendenairbornemuseum. nl). Mocht u geen toegang hebben tot de website, dan kunt u de stukken ook digitaal ontvangen, vanaf twee we-ken vóór de vergadering. Stuurt u hiervoor een verzoek naar secretaris@vriendenairbornemuseum.nl

AGENDA 42E ALV (OCHTEND)

1. Opening 2. Mededelingen en in memoriam 3. Verslag 41ste Algemene Ledenvergadering, d.d. 16 maart 2019 4. Nieuws van het Airborne Museum 5. Verkiezing bestuur 6. Jaaroverzicht 2019 7. Financieel verslag 2019 8. Verslag kascommissie 9. Begroting 2020 10. Situatie Engelse leden en relatie met Arnhem 1944 Fellowship 11. Programma 2020 12. Rondvraag 13. Sluiting

LEZING THE LOST COMPANY (MIDDAG)

’s Middags, na de ALV, zal Marcel Anker een lezing hou-den over The Lost Company: C Company 2nd Parachute Battalion in Oosterbeek and Arnhem September 1944.

De lezing is van 13.00u tot 15.00u (met pauze).

Marcel Anker is als expert van de gevechten rond de Utrechtseweg op 18/19 sept. 1944 geen onbekende bij de Vereniging. Zijn boek uit 2017 The lost company be-schrijft de verrichtingen van C Company tijdens de slag tot in detail. De compagnie kreeg op 17 september de opdracht de spoorbrug bij Oosterbeek te veroveren, wat niet lukte omdat de Duitsers de brug opbliezen. Tijdens de opmars naar het tweede doel, de Arnhemse Ortskom-mandantur, raakte de compagnie verwikkeld in staatge-vechten rond de Utrechtseweg. Tot een link-up met de rest van het bataljon bij de verkeersbrug kwam het niet.

Het gros van de eenheid werd krijgsgevangen gemaakt.

De lezing is gratis voor VVAM-leden. Niet-leden betalen €5 bij binnenkomst.

MEDEDELINGEN

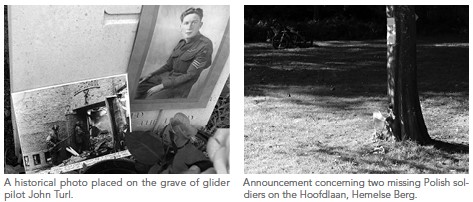

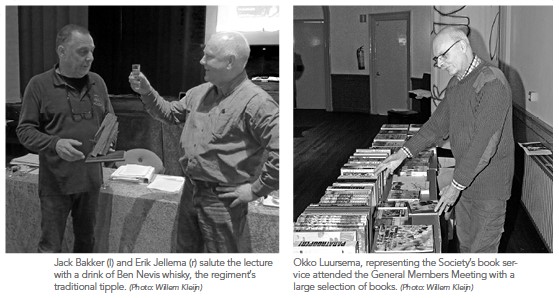

Leden van de vereniging War Department Living History – The Border Regiment tijdens de ‘Boekenbeurs 2.0’ die de VVAM op 13 april 2019 organiseerde (foto’s: website VVAM).

VVAM-CONTRIBUTIE 2020

Om de activiteiten die we als vereniging ontplooien te blijven doen en om de kwaliteit van Airborne Magazine op een hoog peil te houden, hebben we uw contributie hard nodig. De VVAM draait op een aantal onbezoldig-de bestuursleden en is dus afhankelijk van haar betalen-de contribuanten. Daarom enkele mededelingen en een verzoek:

Het VVAM-kalenderjaar loopt van februari tot februari.

Dit betekent dat we uw contributie voor 2020 graag vóór 28 februari ontvangen. In Airborne Magazine nr. 17 (de aprileditie) zullen we u nog een keer notificeren. Indien u daarna alsnog betaalt, ontvangt u de gemiste Airborne Magazines gewoon op het door u opgegeven adres. Let wel: dit betekent ook dat u geen magazines meer krijgt zolang uw contributie niet is overgemaakt.

In november 2020 zullen alle leden die hun contribu-tie nog niet hebben voldaan, nogmaals hieraan worden herinnerd per brief. Wanneer uw betaling niet voldaan is vóór 31 december 2020, zult u uit het ledenbestand worden gehaald. Wij rekenen op uw begrip.

LEDEN EN LEDENADMINISTRATIE

Het aantal VVAM-leden toont een licht stijgende lijn.

Op dit moment zijn dit er 653. Zestien Vrienden hebben om diverse redenen hun lidmaatschap opgezegd. Daar tegenover staat dat we 29 nieuwe Vrienden hebben.

De vereniging gaat volgend jaar gebruik maken van een geautomatiseerde ledenadministratie, waarin bijvoor-beeld ook bankgegevens kunnen worden geïmporteerd.

Als het goed is merkt u weinig van deze overgang. Mocht dit onverhoopt wel zo zijn, neemt u dan gerust contact met ons op.

Tot slot: zou u voor het compleet maken van onze administratie uw e-mailadres aan ons willen doorgeven?

Dit kan op onderstaand adres. – Bernhard Deeterink, ledenadministratie VVAM admin@vriendenairbornemuseum.nl

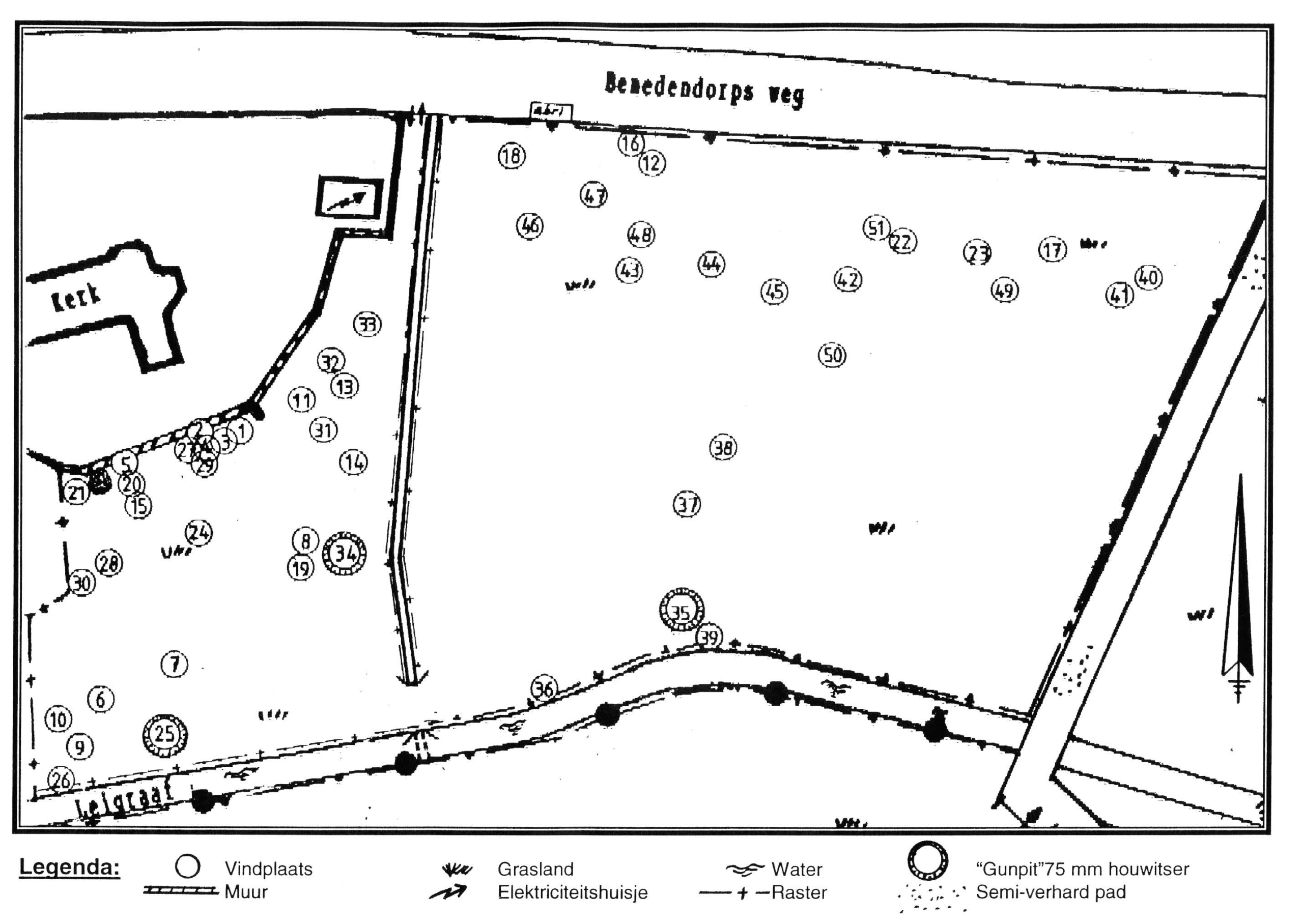

CONFLICTARCHEOLOGIE VILLA HESELBERGH: ARCHEOLOGIE OP EEN DUITS HOOFDKWARTIER IN ARNHEM

Villa Heselbergh. Deze naam zal niet bij elke Tweede Wereldoorlog-kenner direct een bel-letje doen rinkelen. Toch was dit Arnhemse landhuis het centrum van de Duitse gevechts-leiding in de regio Arnhem tijdens de septemberdagen van 1944. Vanwege de herontwik-keling van het terrein heeft in 2018 archeologisch onderzoek plaatsgevonden. Dit leidde tot nieuwe inzichten die meer vertellen over deze bijzondere plek. Het onderzoek is nog in de uitwerkingsfase; in dit artikel zal ik enkele voorlopige resultaten met u delen.

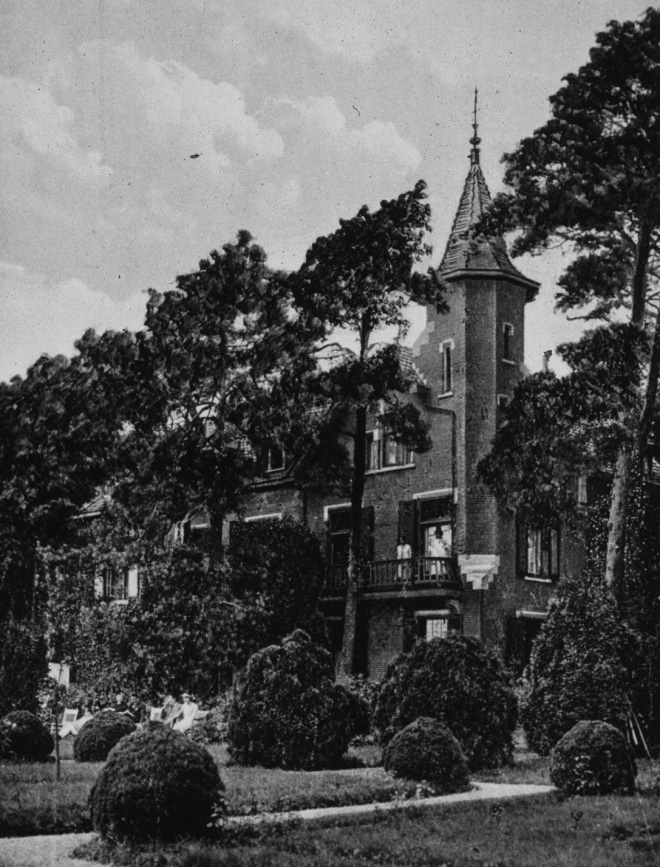

De villa omstreeks 1920 (Gelders Archief: 1501-04 – 1242, Public Domain Mark 1.0 licentie)

BOSCHRYKE OMGEVING

Op de natuurlijk gevormde heuvel langs de Apeldoorn-seweg, even ten noorden van de Arnhemse binnenstad, liet dhr. H.A. Van Leeuwen een villa bouwen voor hem en zijn gezin. De villa in Engelse landhuisstijl werd, samen met een bijgebouw, in 1912 gerealiseerd. Het pand bezat reeds centrale verwarming en beschikte over

koud- en warmwaterleidingen. Van Leeuwen en zijn gezin bewoonden de Heselbergh tot in 1924, waarna de villa ruim vier jaar leeg stond.

De rooms-katholieke stichting Insula Dei kocht de villa in 1928 om dienst te doen als klooster. In eerste instantie voor paters en later voor zusters die werk-zaam waren in het onderwijs. De relatief afgezonderde ligging van de villa maakte de plek bijzonder geschikt voor religieuzen. Zij werden pas in het vierde jaar van de bezetting gedwongen om de villa en het terrein te verlaten.

NEDERLAND BEZET

In mei 1940 werd Nederland bezet door Duitsland.

Vrijwel direct kreeg Nederland een militair opperbe-velhebber toegewezen: de Wehrmachtbefehlshaber in den Niederlanden Friedrich Christiansen (1879-1972). Hij oefende de hoogste territoriale macht uit in het bezette Nederland.

Het gezag van deze Wehrmachtbefehlshaber werd door Kommandanturen in de praktijk gebracht.

Bovenaan in deze hiërarchie stonden Feldkomman-danturen, die elk over hun eigen gebied de territori-ale zaken voor de Wehrmachtbefehlshaber regelden.

Binnen het gebied van een Feldkommandantur waren meerdere Wehrmachtkommandanturen aanwezig, die weer een ander takenpakket hadden. Hieronder ressorteerden de (ständige) Ortskommandanturen, die in elke stad en in vele dorpen aanwezig waren.

FELDKOMMANDANTUR 642

Nederland werd opgedeeld in districten, elk met een Feldkommandantur (FK) aan het hoofd. Tijdens de bezetting wijzigde deze indeling, en daarmee het aan-tal en de locaties van de Feldkommandanturen. In de zomer van 1943 werd een nieuwe, Arnhemse FK aan de lijst toegevoegd. Noord- en Oost-Nederland werden voortaan geleid door de FK 642 ‘Arnheim’.

Commandant werd Generalmajor Friedrich Kussin (1895-1944). Onder hem stond een kleine, adminis-tratieve eenheid van het Heer (landmacht) bestaande uit enkele officieren en vrouwelijke Stabshelferinnen (typistes, telefonistes, etc.). De villa werd het stafkan-toor en dus de werkplek van de FK. Het personeel werd ondergebracht in villa’s in de buurt. Zo werd landhuis ’t Waelre (Braamweg 4) Kussins woning.

Een belangrijke historische bron over de Heselbergh als FK is een verzetsrapport van de Groep Albrecht. In juni 1944 noemden zij onder andere dat om het vil-laterrein een prikkeldraadversperring is aangebracht.

Bovendien hebben de Duitsers opstelplaatsen voor voertuigen gegraven: half ingegraven parkeerplaatsen voor voertuigen met aan drie zijden een aarden wal.

Tot slot was op de noordzijde van het terrein een ‘zwa-re schuilplaats’ aangelegd en was het dak van de villa voorzien van antennes.

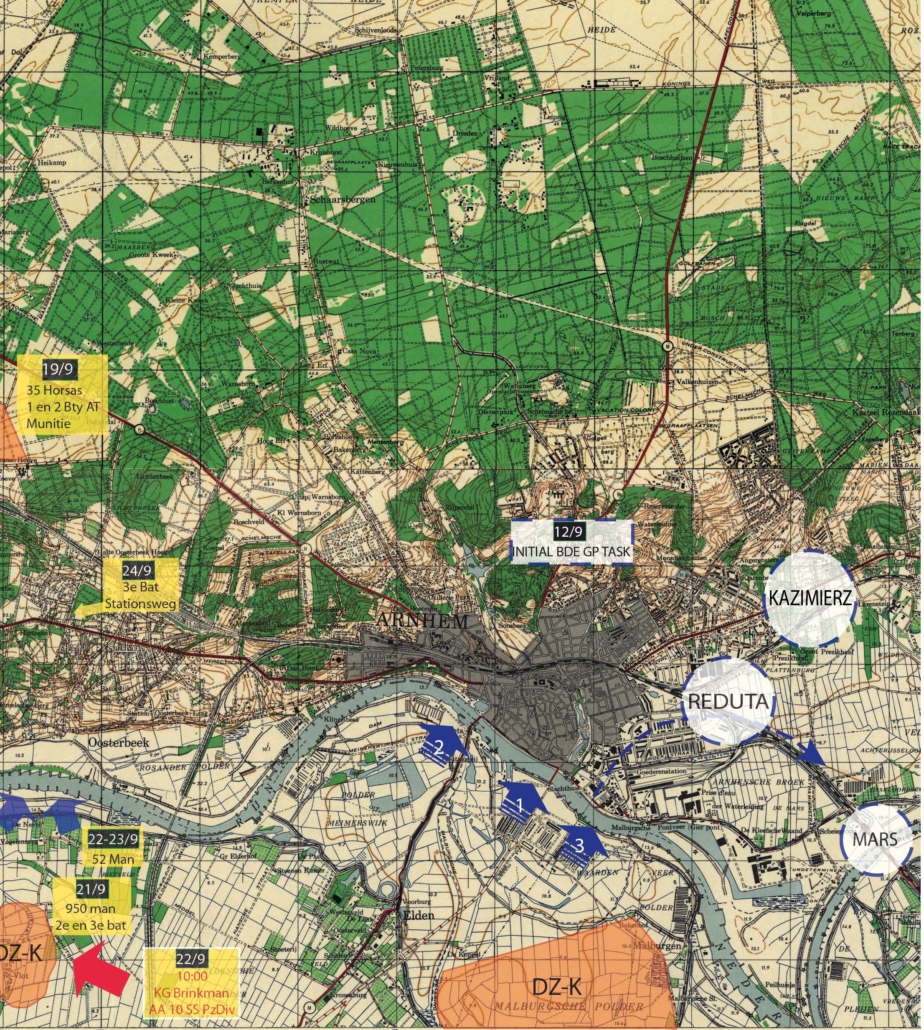

MARKET GARDEN

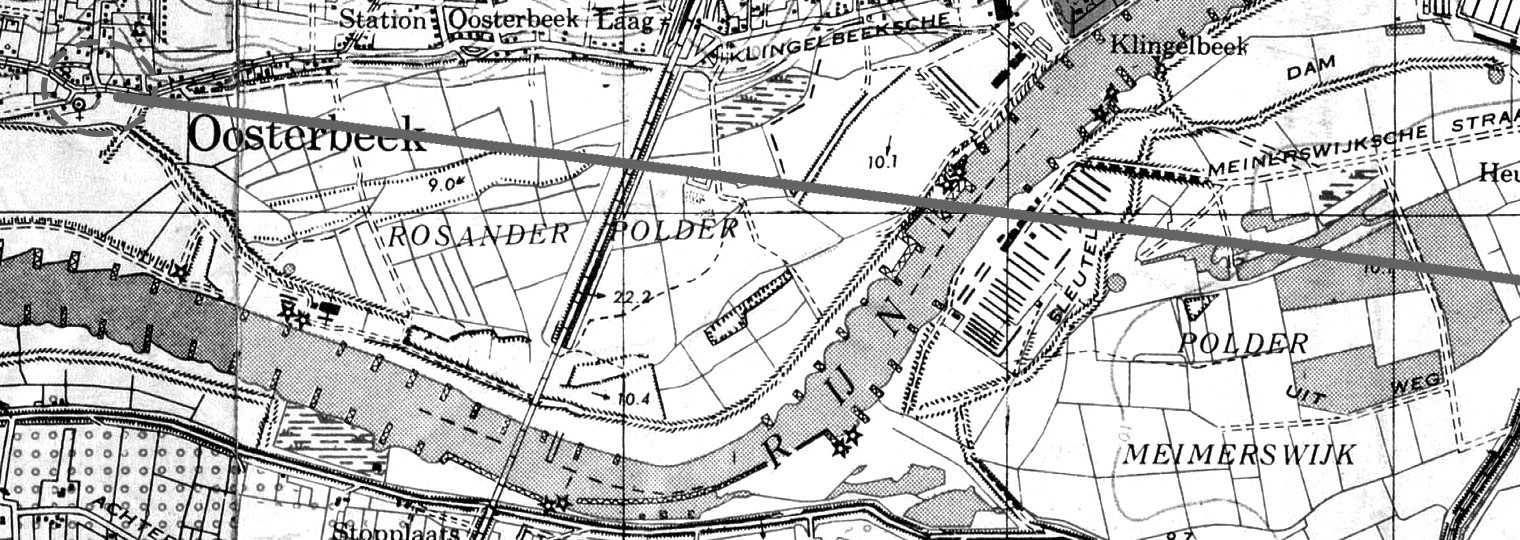

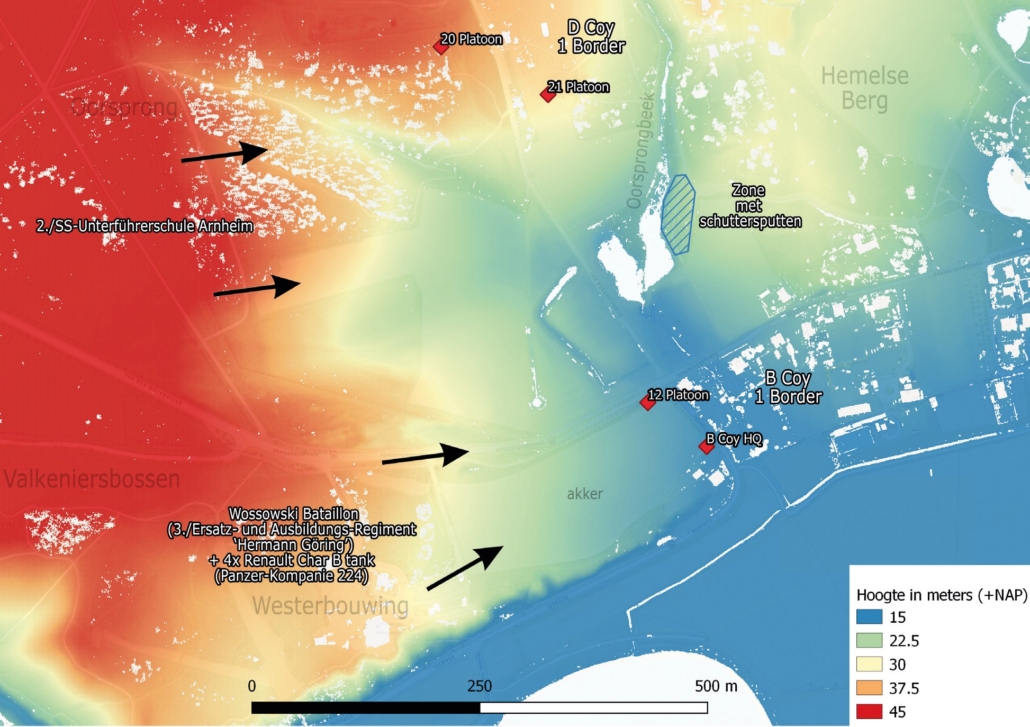

Toen op 17 september 1944 operatie Market Gar-den van start ging, bleef het personeel van de FK op zijn post. Dit in tegenstelling tot bijvoorbeeld de Ortskommandantur, die direct naar Dieren werd ver-plaatst. Een Feldkommandantur was onder meer ver-antwoordelijk voor het overzicht van de in hun sector aanwezige eenheden. Dit zou kunnen verklaren waar-om Generalmajor Kussin poolshoogte ging nemen bij de SS-opleidingseenheid onder het commando van SS-Obersturmbannführer Sepp Krafft. Zij waren tus-sen Oosterbeek en Wolfheze in stelling gegaan. Hier bezorgden zij de Britten die de Tiger-route (Utrecht-seweg) volgden enig oponthoud.

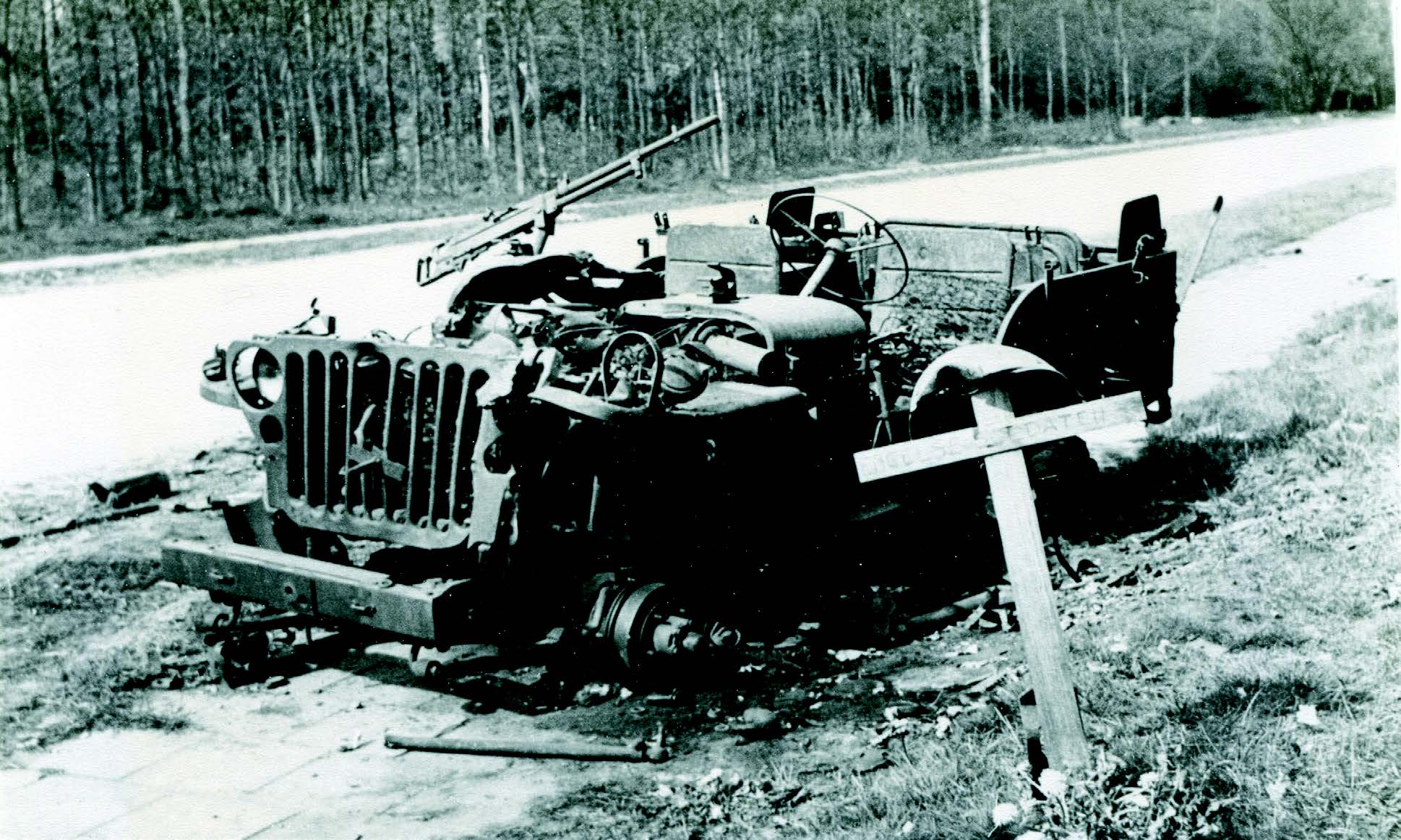

Op de terugweg ging het echter mis en werd de auto van Kussin, inclusief diens chauffeur, adjudant en tolk, doorzeefd met Britse kogels. Alle vier inzitten-den kwamen bij deze actie om. Deze gebeurtenis is wijd bekend vanwege het (bewegend) beeldmateriaal van de doorzeefde auto en de stoffelijke overschotten.

De Britten begroeven de vier van FK 642 in een veld-graf langs de weg, waarmee ze in eerste instantie als ‘vermist’ te boek kwamen te staan aan Duitse zijde.

Nog dezelfde avond werd daarom het commando overgenomen door de 47-jarige Major Ernst Schlei-fenbaum, die al werkzaam was bij de staf van Kussin.

HARZERS HOHENSTAUFEN-DIVISIE

Terwijl Feldkommandantur 642 gebruik bleef maken van Villa Heselbergh, werd de locatie ’s avonds ook toegewezen als stafkwartier voor de 9. SS-Panzerdi-vision ‘Hohenstaufen’. Beide stafeenheden waren dus gelijktijdig in de Arnhemse villa ondergebracht. De ligging net buiten het centrum en de aanwezige ver-bindingen zullen hierin doorslaggevend zijn geweest.

De Hohenstaufen-divisie onder het (tijdelijke) com-mando van SS-Obersturmbannführer Walter Harzer was sinds begin september aanwezig op de Veluwe-zoom nadat zij met zware verliezen uit Noord-Frank-rijk waren teruggetrokken. Al in de eerste uren van Market Garden vormde Harzer gevechtsgroepen ten noorden van de Rijn.

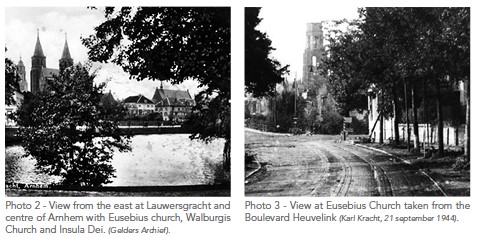

GEVECHTSLEIDING

Het maakt de Heselbergh tot een uitzonderlijke lo-catie omdat op dit hoofdkwartier veel bevelhebbers uit de regio samen kwamen en vergaderden. De villa werd bezocht door onder meer Feldmarschall Walter Model (Heeresgruppe B), SS-Obergruppenführer en General der Waffen-SS Wilhelm Bittrich (II. SS-Pan-zerkorps) en SS-Brigadeführer Heinz Harmel (10.

SS-Panzerdivision ‘Frundsberg’).

De FK kwam, net als de Hohenstaufen- en Frunds-berg-divisie, onder het bevel te staan van het II.

SS-Panzerkorps van Bittrich. Specifieke taken tijdens de gevechten zijn niet bekend, maar het is zeker dat de FK actief bleef tot en met 21 september. Op die dag werd de noordelijke oprit van de Arnhemse ver-keersbrug op de Britten heroverd. Een deel van het personeel van de FK, waaronder de Stabshelferinnen Margret Hermes en Gerdi Lücking, werd vanwege hun optreden tijdens de slag om Arnhem zelfs geno-mineerd voor een Duitse onderscheiding, die zij en-kele maanden later ontvingen. Op de 21e werd het commando van FK 642 overgenomen door Oberst Von Gröling (commandant van de Truppenübungs-platz Harskamp) en vertrok de eenheid naar Warns-veld bij Zutphen, en nog later naar het achterland in Almelo.

De Divisionsstab van Harzer bleef langer op de Hesel-bergh. De geallieerde luchtlandingseenheden waren inmiddels teruggetrokken op Oosterbeek en vormden

daar een zogeheten perimeter. De Hohenstaufen-divi-sie en daaronder ressorterende eenheden bestookten de geallieerden constant. Ook deze gevechten werden geleid vanuit Villa Heselbergh. De restanten van 1st Airborne Divison hielden het uit tot de nacht van 25 op 26 september en trokken zich terug over de Nederrijn.

Bespreking in Villa Heselbergh. Van links naar rechts: Model, Harmel, Student, Bittrich en dáárachter Harzer (foto: PK Adendorf, BArch-MA Freiburg).

KRIJGSGEVANGENEN

Een deel van de Britse krijgsgevangenen werd on-dervraagd door de inlichtingendienst van de Hohen-staufen-divisie, die zich bevond in de nabijgelegen School 8. Ze werden ondergebracht in de weide bij de naastgelegen Braamberg. In de tuin van de villa zelf zou ook een klein kamp aanwezig zijn geweest.

De Airbornes werden hierna naar een verzamelplaats binnen het terrein van Fliegerhorst Deelen gebracht.

Ook het speciaal hiervoor ingerichte Durchgangslager op de Harskamp zag enige tijd gevangen geallieerde luchtlandingstroepen.

GEVECHTSPAUZE

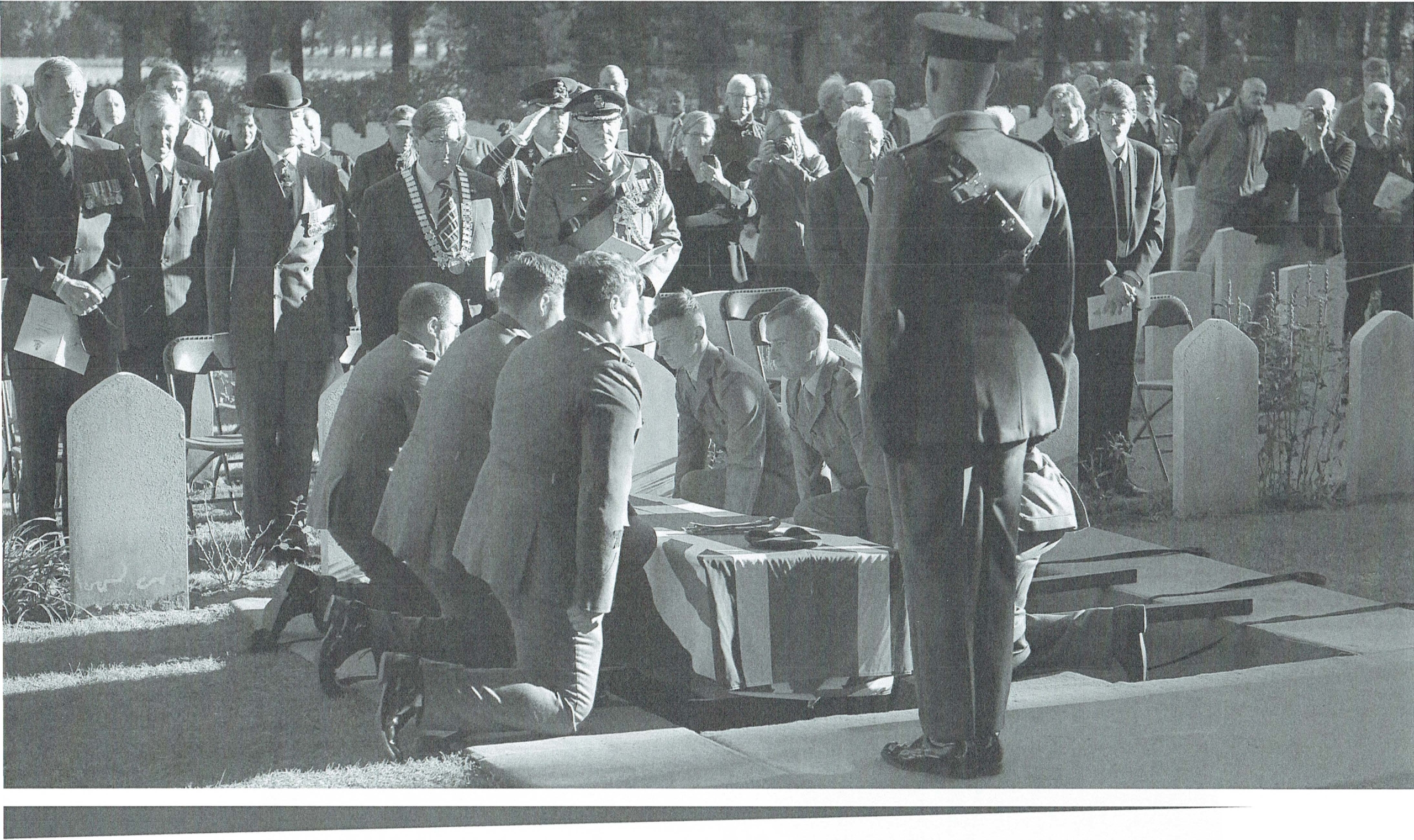

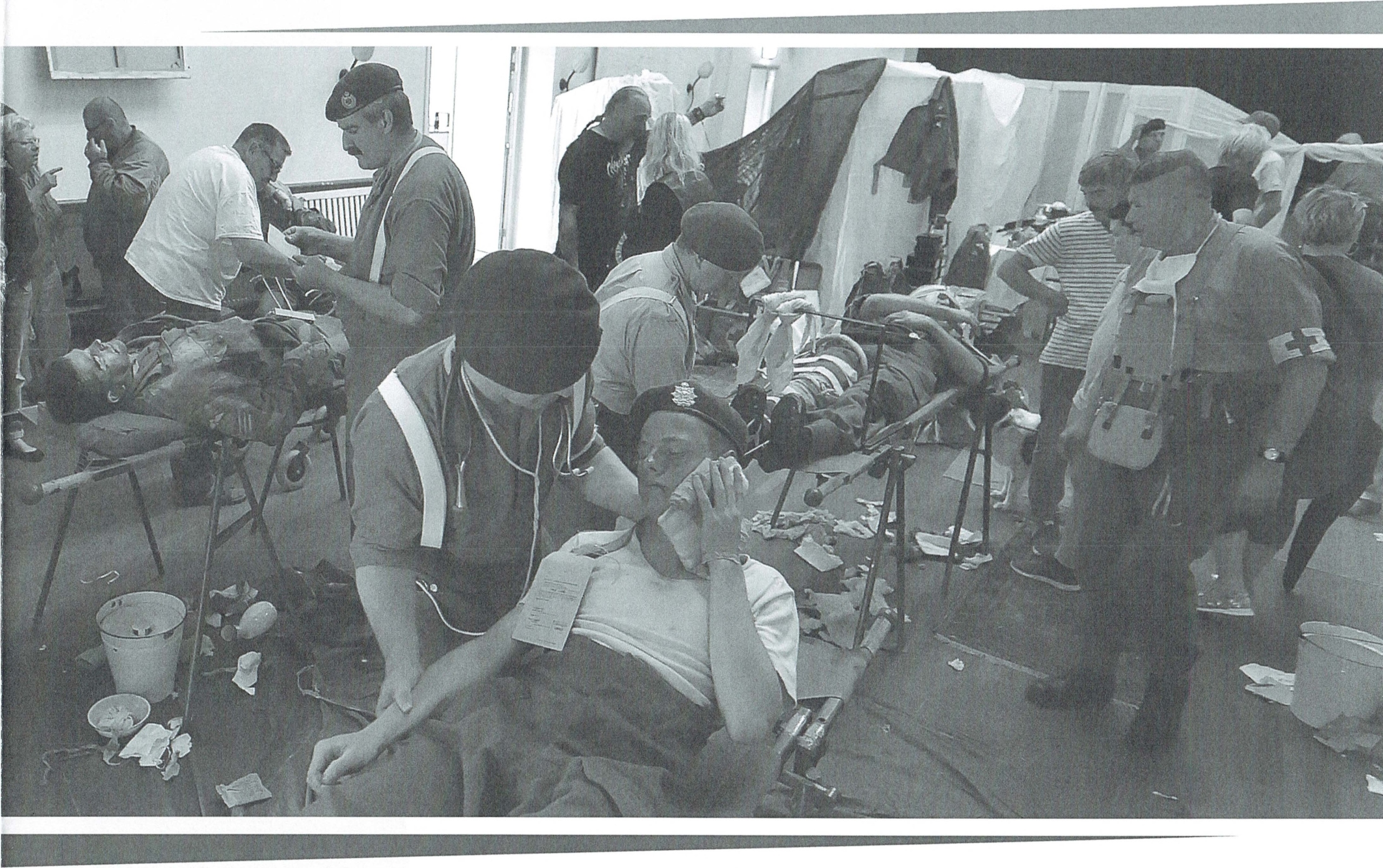

Bijzonder is ook dat op de locatie onderhandelingen hebben plaatsgevonden. De Duitse staf ontving het Nederlandse Roode Kruis en zelfs Britse militairen op de Heselbergh. Na dagenlange gevechten lagen er circa 1.200 gewonden van beide strijdende partijen in het relatief kleine gevechtsgebied in Oosterbeek.

Colonel Graeme Warrack, verantwoordelijk voor de medische verzorging van de Britse luchtlandingseen-heden zag met de uitpuilende noodhospitalen geen andere optie meer dan het organiseren van een tijde-lijke wapenstilstand. Warrack kreeg als tolk de Ne-derlandse militair in Brits uniform Arnoldus Wolters toegewezen. Vanwege het risico om geëxecuteerd te worden als ‘partizaan’, kreeg Wolters een Britse naam: Johnson.

Het gezelschap begaf zich naar een nabijgelegen Duits noodhospitaal waar zij in contact kwamen met SS-Hauptsturmführer Dr. Egon Skalka. Skalka was verantwoordelijk voor het medisch verzorgings-gebied van de Hohenstaufen-divisie. Skalka begreep het standpunt van de Britten en wilde ingaan op het voorstel. Hij reed daarom Warrack en ‘Johnson’ (zon-der blinddoek) in een buitgemaakte Britse jeep naar zijn stafkwartier.

De bespreking zoals weergegeven in de film A Bridge too Far (Sony Pictures Home Entertainment, film still, 1977).

Warrack schreef na de oorlog over zijn bezoek aan de Heselbergh, onder meer dat Bittrich tegen hem zei dat “het hem erg speet dat het oorlog was tussen onze landen”, en dat hij op zijn verzoek in zou gaan. Die dag konden circa 450 gewonde Britten en Duitsers worden afgevoerd naar veiliger oorden. De bespreking tussen Warrack, Wolters, Skalka en Bittrich op de He-selbergh is verfilmd in A Bridge Too Far (1977).

ONTRUIMING

Direct na de geallieerde terugtocht over de Nederrijn was het enkele dagen relatief rustig in de regio. Vijf dagen later, op 30 september 1944, kreeg de Hohen-staufen-divisie bevel om richting Siegen in Duitsland te trekken. Hun taak in de regio zat er op. De staf zal ergens begin oktober de Heselbergh hebben ver-laten. Na een korte bezetting door de Einsatzstab van Organisation Todt (OT) in november, bleef de villa hoogstwaarschijnlijk leeg staan. Doordat de stroom- en watertoevoer was uitgevallen, werden er zelfs geen dwangarbeiders van de OT ondergebracht. Met de geallieerde artilleriebeschietingen in april 1945 voor-afgaand aan de IJsseloversteek en de zuivering van Arnhem is Villa Heselbergh verwoest. Deze was toen niet meer bezet door Duitse eenheden.

ARCHEOLOGIE OP DE HESELBERGH

In 2018 werd de naoorlogse bebouwing op de loca-tie gesloopt voor nieuwbouw, die inmiddels is opge-leverd onder de naam Silhouet. Het archeologisch veldonderzoek is uitgevoerd door Greenhouse Advies (DAGnl) met ondersteuning van Military Legacy.

Hieronder volgen een paar resultaten:

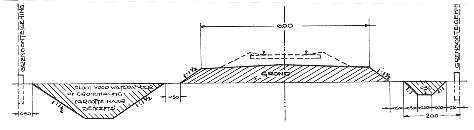

1. Kussins schuilkelder Opmerkelijk was de vondst van (een deel van) de schuilkelder van Feldkommandatur 642, die ook door het verzet werd genoemd. De ingang met trap-partij bevond zich in het zuidwesten, het dichtst bij de villa. Op vooroorlogse foto’s van de villa is te zien dat hier een loggia aanwezig was: een open ruimte voorzien van zuilen. De ingang van de schuilkelder bevond zich op het dichtstbijzijnde punt van de ope-ning van deze loggia. Hierachter was ook een deur naar de villa aanwezig.

De schuilkelder van de Heselbergh komt qua type overeen met andere Duitse Luftschutzräume, zoals ook zijn aangetroffen op bijvoorbeeld het kazerneter-rein in Venlo. Parallellen met schuilkelders op locaties waar zich hoge Duitse officieren bevonden bestaan met die van andere belangrijke (staf)kantoren, zoals die van Reichskommissar für die Niederlande Arthur Seyss-Inquart op landgoed Clingendael (Den Haag) en nabij Paleis Het Loo (Apeldoorn). Beide laatstge-noemde bunkers zijn van een ander (groter, zwaar-der) type. Opvallend daarbij is dat voor Generalmajor Kussin en zijn staf ‘slechts’ een standaardtype schuilkelder werd gebouwd, die ook op kazernes voor reguliere infanterie werd toegepast. Gesteld zou kunnen worden dat hier sprake was van een vorm van hiërarchie in importantie.

De schuilkelder was opgevuld met materiaal, waar-onder vijf brandstofvaten van elk 200 liter met reli-eftekst op de deksels (‘Wehrmacht Feuergefährlich 1943’). Bij de ingang lag een vooroorlogse brandblus-ser (type ‘snelblusscher’ van het merk Vlaminax). Een deel hiervan zal worden geconserveerd en bewaard. 2. Body armour Geallieerd materiaal is tijdens het onderzoek nauwelijks aangetroffen, op enkele kleinkaliberhulzen na. Opvallend is een restant van een Brits ‘body armour’-vest uit de vulling van de schuilkelder. Dit scherfwerende uitrustingsstuk werd in eerste instantie voornamelijk uitgereikt aan Britse en Poolse luchtlandingseenheden. Bekend is dat krijgsgevangenen wer-den ondervraagd door de inlichtingendienst van de Hohenstaufen-divisie die in de nabijgelegen School 8 was gevestigd. De Britten werden daar, maar waarschijnlijk ook in de tuin van Villa Heselbergh, tijde-lijk ondergebracht. Het dragen van body armour was tijdens de Tweede Wereldoorlog zeker niet gewoon.

Het is mogelijk dat het object uit curiositeit op het Duitse hoofdkwartier terecht is gekomen. De vondst

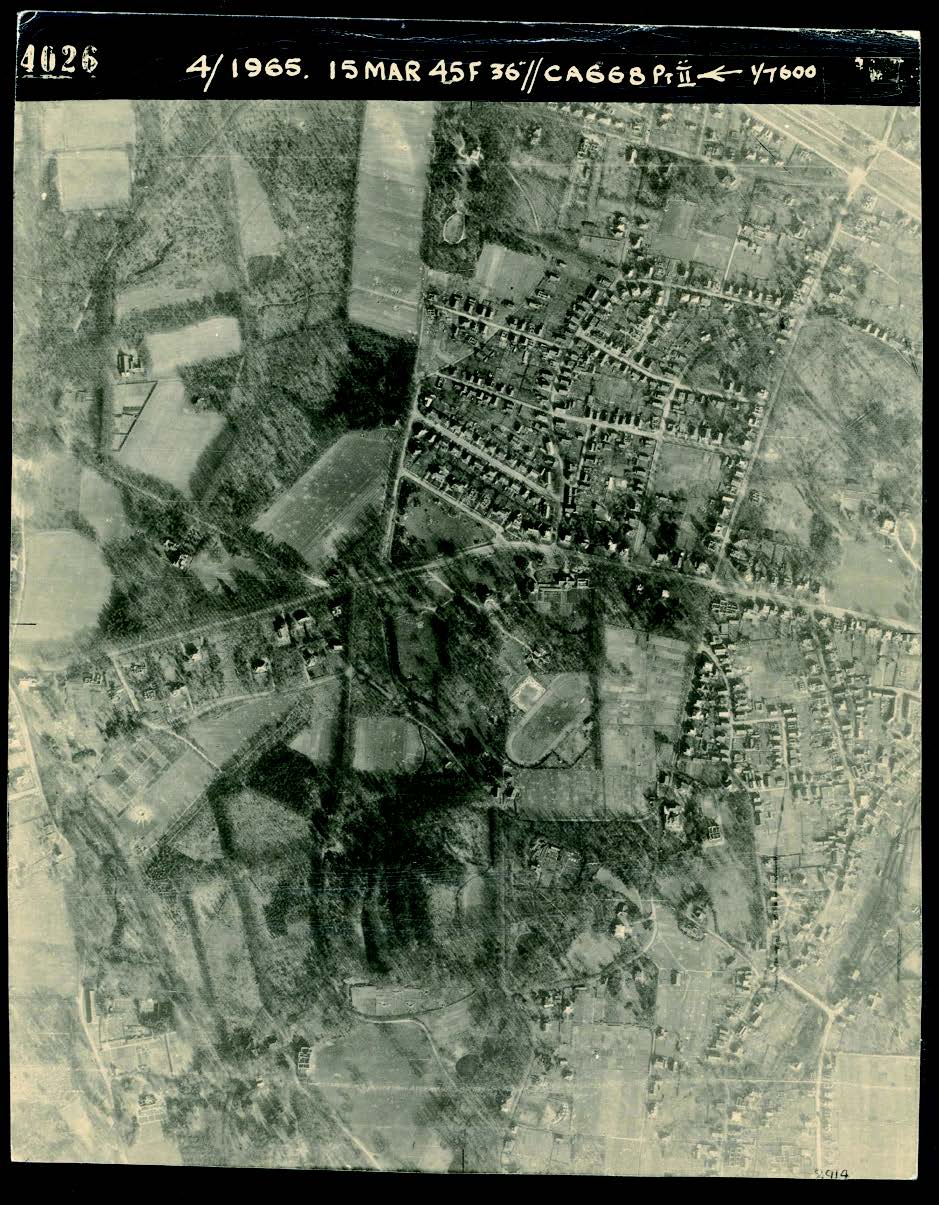

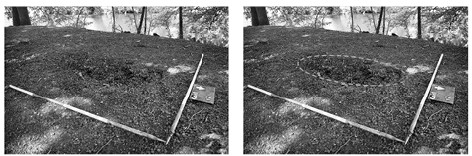

lijkt dan ook zeer waarschijnlijk gekoppeld te kunnen worden aan de slag om Arnhem, en aan de aanwezige Britse krijgsgevangenen. 3. Kussins parkeerplaats Zuidelijk van het plangebied liep en loopt de Braam-weg. In deze randzone zijn op geallieerde luchtver-kenningsfoto’s twee Duitse voertuigopstelplaatsen (Kraftfahrzeug-Splitterboxen) zichtbaar. Deze parkeerplaatsen waren in het steile talud uitgegraven.

In beide zijn twee proefputten gegraven om de bodemopbouw te registreren.

Beide Splitterboxen geven nagenoeg hetzelfde beeld.

Op 90-120 cm beneden het maaiveld werd een tien centimeter dikke laag met (ijzer)slakken en gesmol-ten glas aangetroffen, die waarschijnlijk als verharding voor de voertuigen heeft gediend. Hieronder was de natuurlijke bodem aanwezig. De maximale diepte van de parkeerplaats komt hierdoor op 1,2 meter. Omdat deze diepte geen bescherming biedt voor bijvoorbeeld een militaire vrachtwagen, is het waarschijnlijk dat de uitgegraven grond als een wal om het spoor heen lag.

Op die manier werd de opstelplaats dus dieper. Dit bovengrondse deel van het spoor is niet (meer) zichtbaar.

Foto van het veldonderzoek: de schuilkelder (foto: A.V.A.J. Bosman / Greenhouse Advies).

De locatie even ten oosten van een belangrijke hoofd-weg (Apeldoornseweg), schuin tegenover de woning van Kussin (Braamweg 4) en nabij de villa (zijn kan-toor) maakt het vrijwel zeker dat de parkeerplaatsen bedoeld waren voor de Feldkommandantur. Het is in dit licht boeiend dat Kussins Citroën Traction Avant hier waarschijnlijk vaak geparkeerd heeft gestaan. Een ongelukkige samenkomst tijdens de eerste uren van Market Garden zorgde ervoor dat alle vier inzittenden van deze Traction hun einde vonden door Brits vuur op de splitsing Utrechtseweg-Wolfhezerweg, zoals hierboven al beschreven.

4. Stahlhelm en Stielhandgranate Tussen het huidige maaiveld en de verhardingslaag van de parkeerplek bevindt zich één dik pakket met materiaal, voornamelijk bestaande uit huisraad en constructiemateriaal van de villa. Hiertussen werd echter ook militaire uitrusting (een Stahlhelm M42

met verfresten) en munitie (de kop van een Stielhand-granate M24) aangetroffen. Dit dateert de afvallaag naar alle waarschijnlijk in de opruimperiode (vlak) na de oorlog.

TOT SLOT

De Heselbergh neemt als locatie een belangrijke rol in bij het verhaal van de Tweede Wereldoorlog en de slag om Arnhem in het bijzonder. De veelzijdige gebeurtenissen die hier tussen zomer 1943 en april 1945 hebben plaatsgevonden (gevechtsleiding, on-derhandelingen, onderdrukking, fusillades en gealli-eerde beschietingen) bleken in het bodemarchief ver-tegenwoordigd. Een deel hiervan is in dit korte artikel besproken. Nader onderzoek in het eindrapport zal een totaalbeeld en meer detailinformatie geven. – Martijn Reinders

GESELECTEERDE BRONNEN UIT HET ARCHEOLOGISCH EINDRAPPORT DAT IN VOORBEREIDING IS:

Archief • Bundesarchiv-Militärarchiv (BArch-MA), Freiburg im Breisgau (Duitsland). RW 37/14. Wehrmacht-befehlshaber in den Niederlanden. Dienstanweis-ung für Feld-, Wehrmacht- und Ortskommandan-turen in den Niederlanden 1943. • Instituut voor Oorlogs-, Holocaust- en Genocide-studies (NIOD), Amsterdam. 190a. Groep Albrecht.

OB 44.

Literatuur • Iddekinge, P.R.A. van, 1981. Arnhem 44/45. Evacuatie, verwoesting, plundering, bevrijding, terugkeer, Arnhem. • Middlebrook, M., 1994. Arnhem. Ooggetuigen-verslagen van de Slag om Arnhem. 17-26 septem-ber 1944, Baarn. • Reinders, Ph., 2012. Medical Research Council, Body Armour and Airborne Helmet Flashes in ge-neral and during the Battle of Arnhem, September 1944, Velp. • Reinders, M., & Bex, J., in prep.: Archeologisch

onderzoek Silhouet (Villa Heselbergh) te Arnhem.

Opgraving • Variant Archeologische begeleiding (Greenhouse Advies-rapport 2018.15). • Revell, S., 2015a: A piece of coloured ribbon. An insight into German Award Winners at the Battle of Arnhem. • Revell, S., 2015b: De dood van een Duitse ge-neraal tijdens de Slag om Arnhem, deel 1, in: Nieuwsbrief Vrienden van het Airborne Museum, Ministory 123 (nr. 6 2015). • Tieke, W., 1978: Im Feuersturm letzter Kriegsjah-re. II. SS-Panzerkorps mit 9. SS-Panzerdivision “Hohenstaufen” und 10. SS-Panzerdivision “Frundsberg”, Osnabrück. • Warrack, G., 1984: Tocht door het duister. Ontsnapping na de slag om Arnhem, Amsterdam.

Met dank aan: L. Buist (Doorwerth), B. Gerritsen (Duiven), I. Jacobs (Nijmegen), S. Revell (Brisbane, Australië), H. Timmerman (Arnhem) en N. Warmerdam (Utrecht).

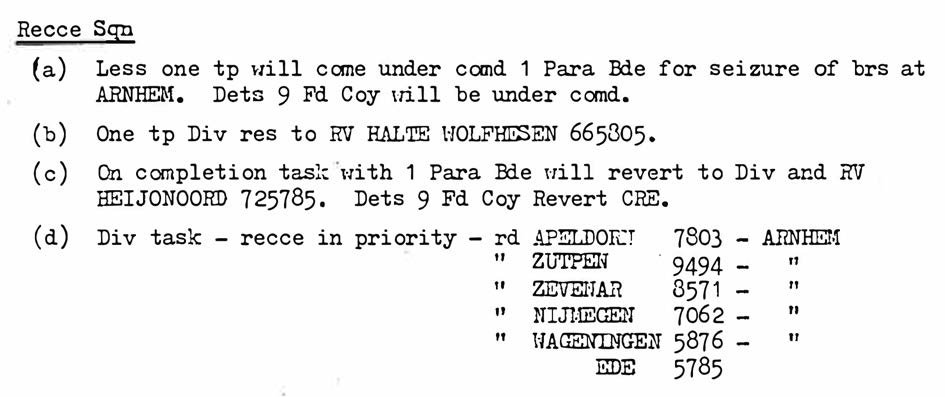

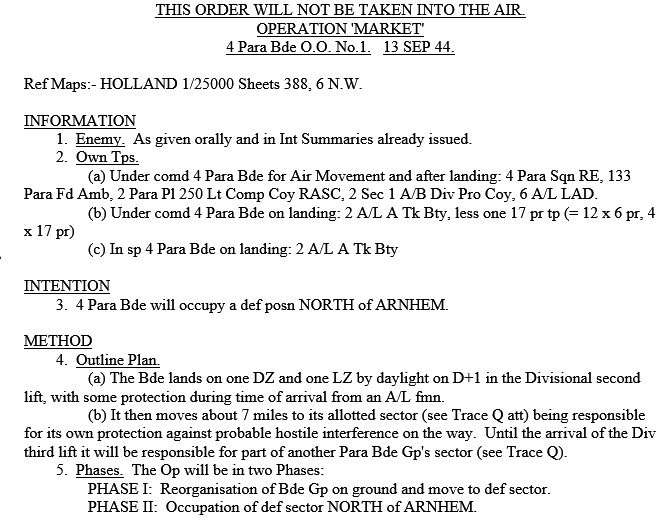

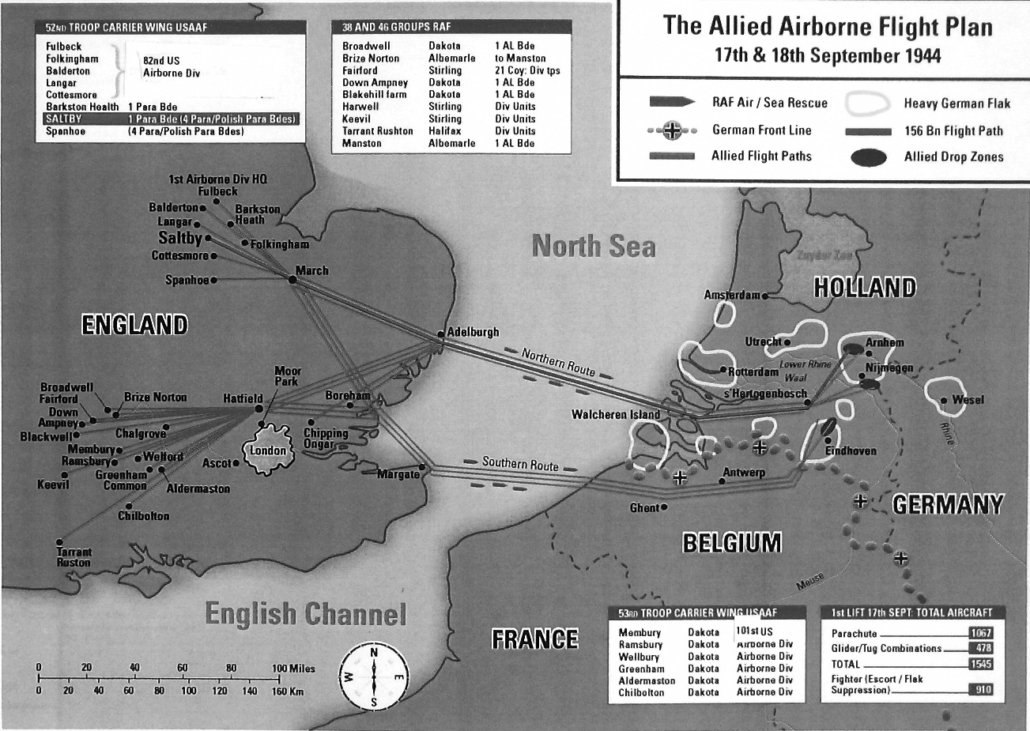

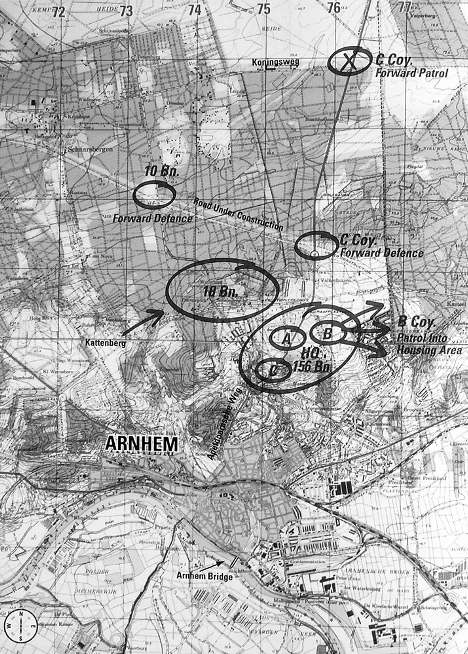

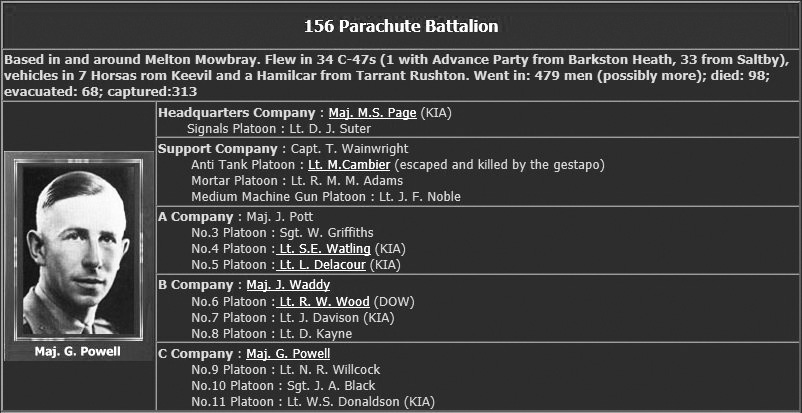

“RACE AHEAD AND GRAB THE ROAD BRIDGE AT ARNHEM” – DE COUP DE MAIN VAN RECCE SQUADRON DIE NOOIT PLAATSVOND

Wat een snelle verrassingsaanval had moeten worden op de verkeersbrug in Arnhem met ruim 200 man eindigde, zoals op zoveel momenten tijdens de slag om Arnhem, met wat de Britten eufemistisch ‘a bloody nose’ noemen. Het verhaal van 1st Airborne Reconnaissance (‘Recce’) Squadron is daarmee bijna exemplarisch voor het verloop van een strijd die werd gevoed door tegenslagen, verkeerde beslissingen, verwoede pogingen en domme pech.

Slechts een paar handjes vol konden na de gevechten in Nederland het glas heffen op het leven in de squadron pub in hun thuisbasis in Lincolnshire.

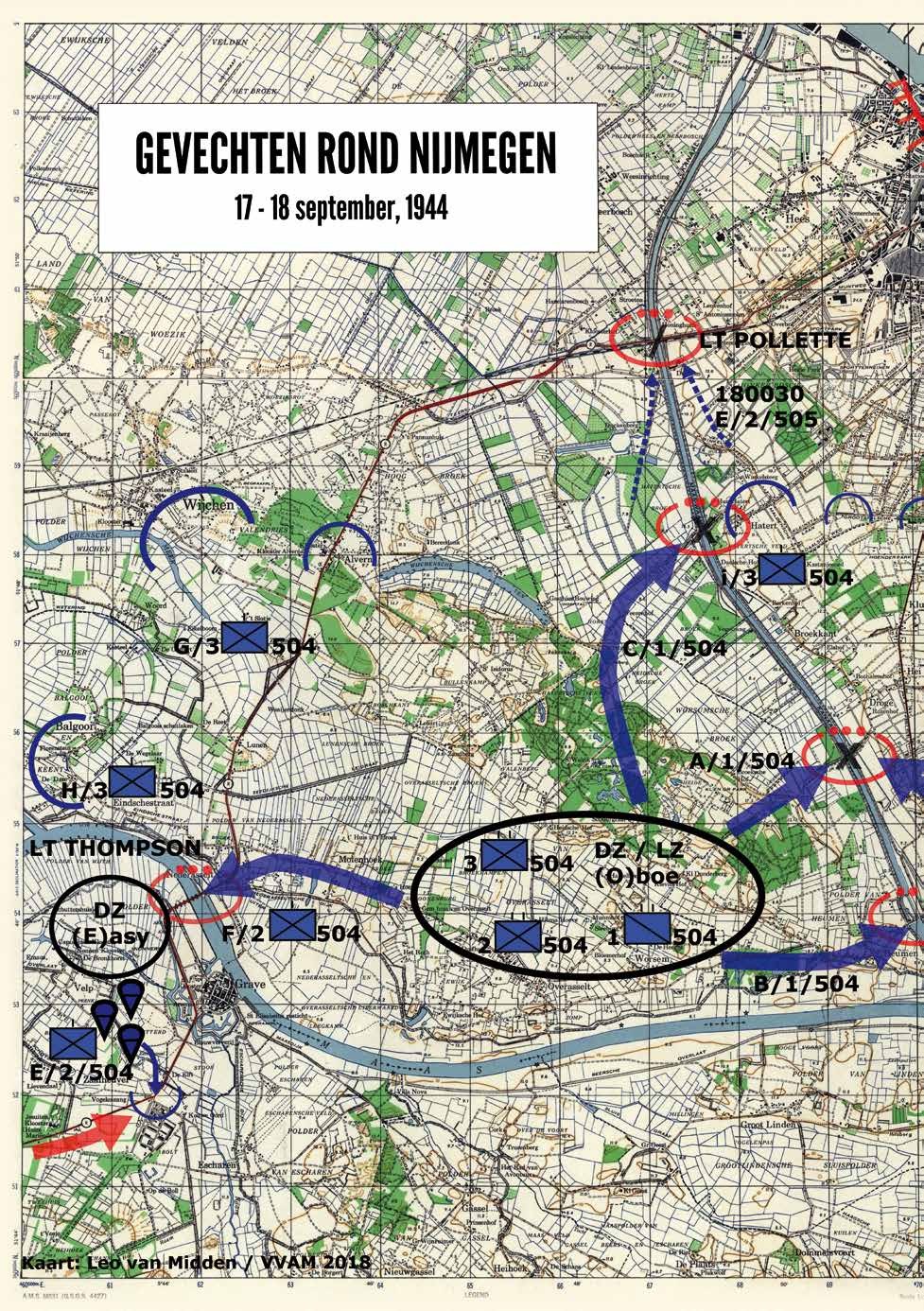

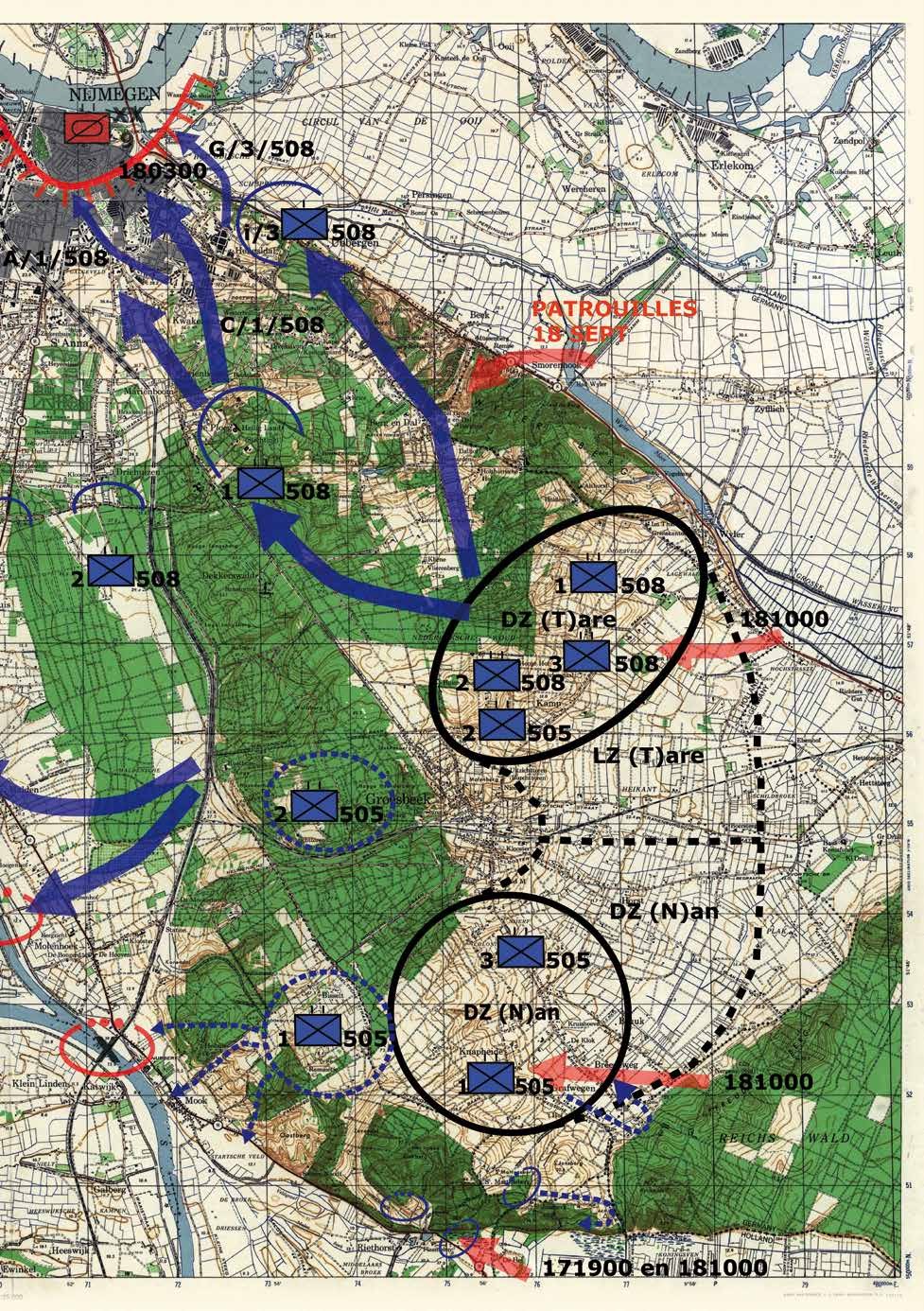

EEN BIJZONDERE OPDRACHT

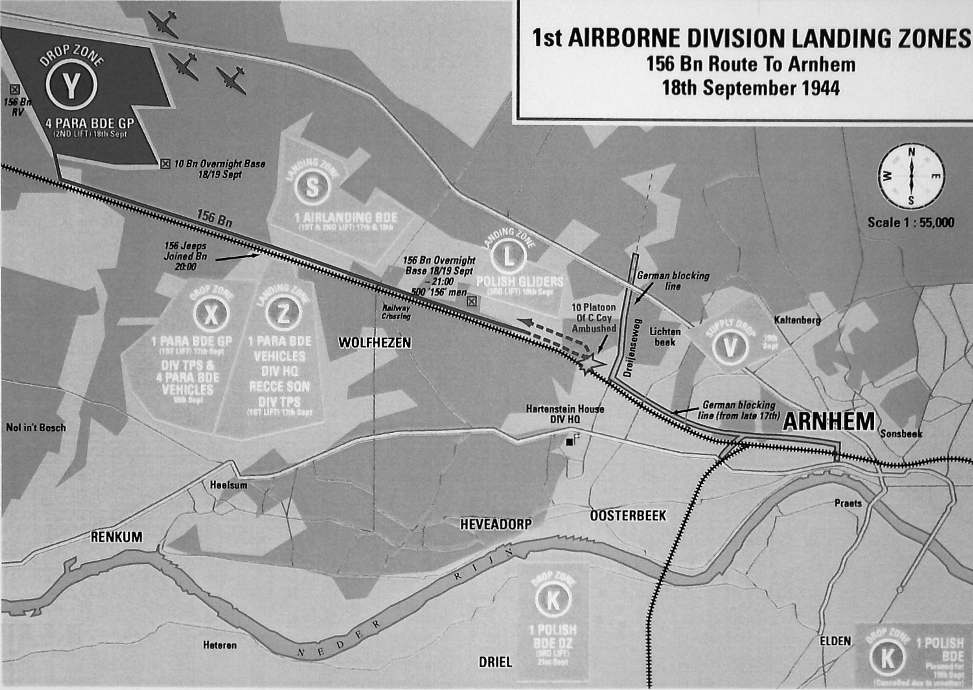

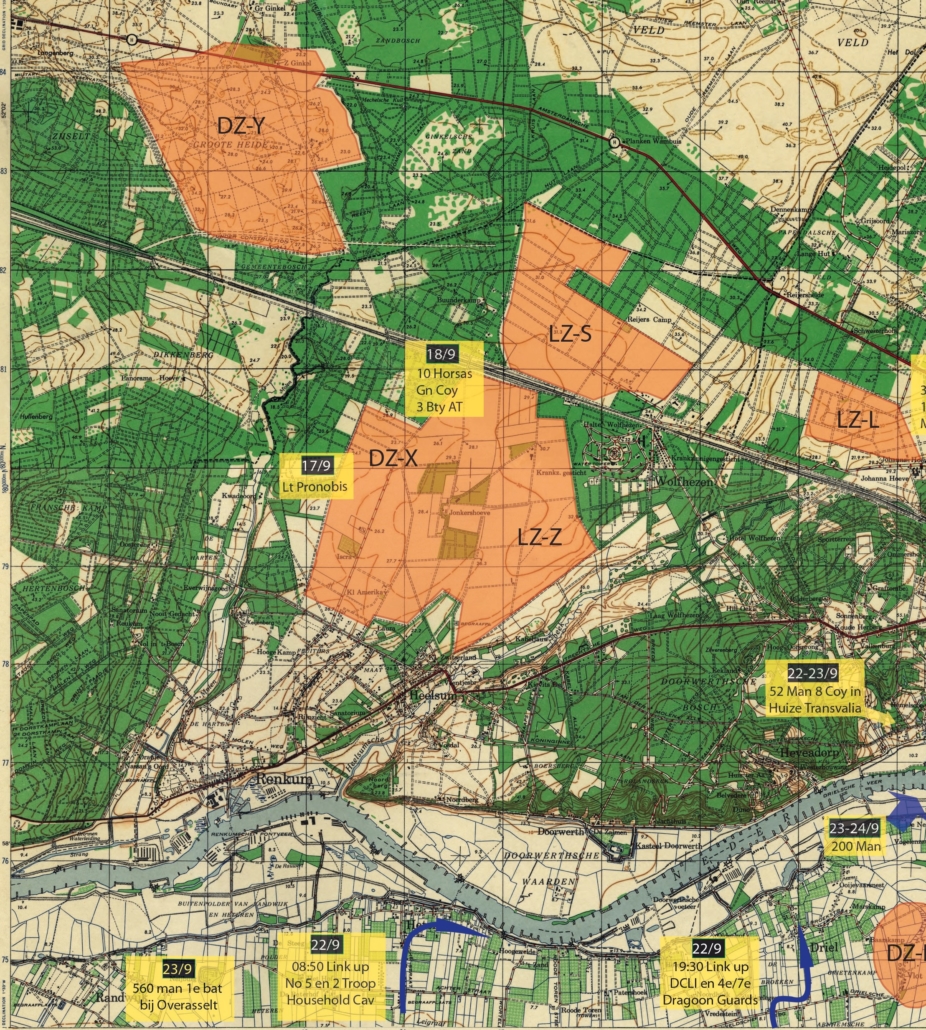

1st Airborne Reconnaissance Squadron stond vóór Market, de codenaam voor het Airbornedeel van ope-ratie Market Garden, onder bevel van 1st Parachute Brigade. Na de gliderlandingen op Landing Zone Z in de middag van 17 september 1944 had het de taak te zorgen voor een rendez-vous met de parachutisten van het squadron op Drop Zone X. Daarna moest een deel van de eenheid, aangevuld met genie, een coup de main (verrassingsaanval) uitvoeren op de verkeers-brug in Arnhem, om deze bezet te houden voor de troepen van 1st Parachute Brigade die te voet naar het doel zouden marcheren.

Populair gezegd: “A special force equipped with jeeps with machine-guns mounted on the bonnet would

race ahead of the main force and grab the road bridge (s) at Arnhem”.

Opdracht aan het squadron, zoals verwoord in de operational instruction van de divisie.

OPRICHTING VAN HET SQUADRON

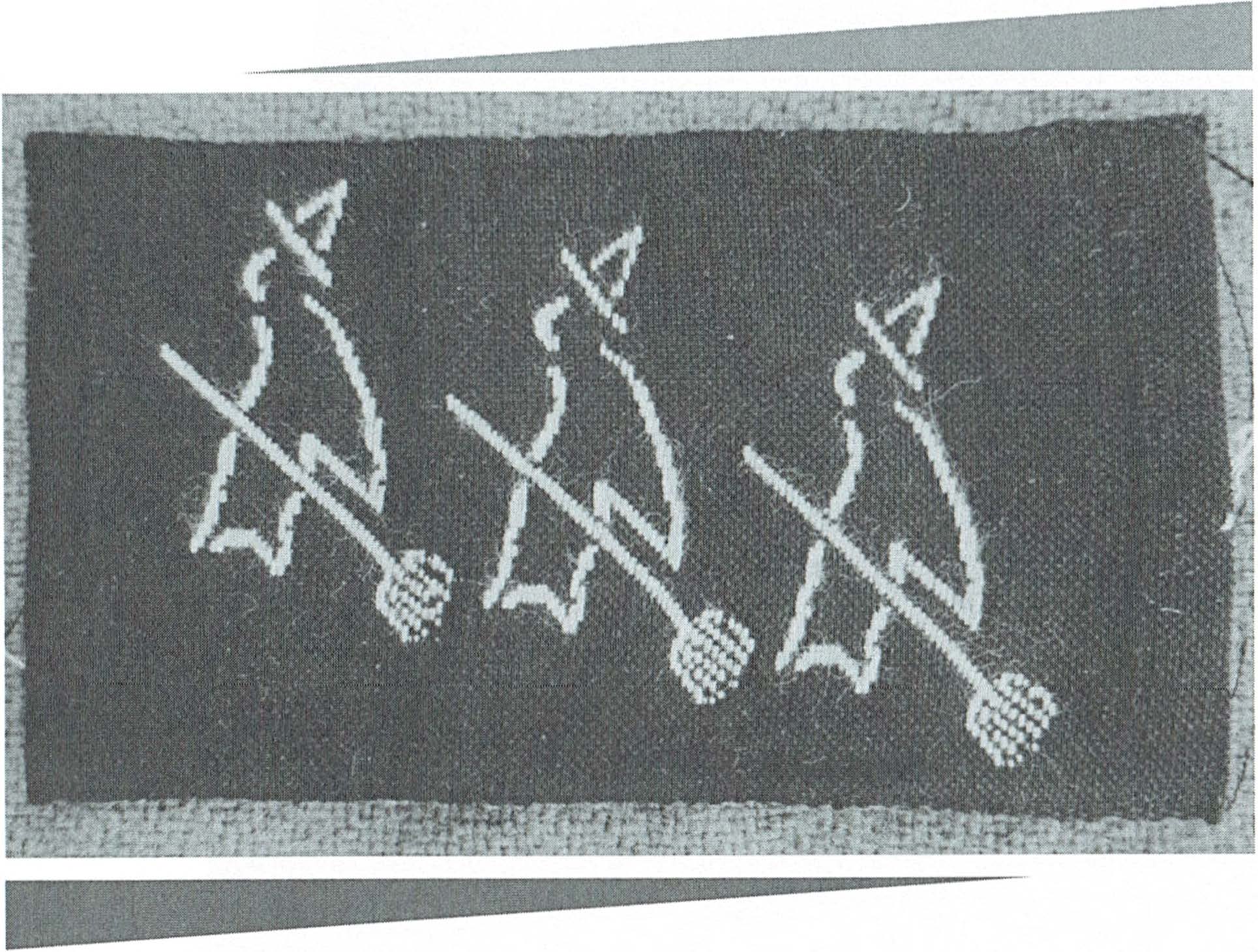

Op 22 juni 1940 schreef Churchill een memo dat re-sulteerde in de oprichting van Britse luchtlandingseen-heden. In 1941 ontstond het Reconnaissance Corps, met vanaf december van dat jaar het 1st Airborne Re-connaissance Squadron in zijn gelederen. Op 25 sep-tember 1941 werden de nieuwe Airbornebadges uitge-reikt aan het squadron; Major Terence Otway was op dat moment commandant van de eenheid (Otway zou drie jaar later bekendheid verwerven met de aanval op Merville Battery in Normandië tijdens D-Day). Kort daarop, op 22 november 1941, nam Major Freddie Gough het commando over. In december 1941 con-verteerde de 31 (Independent) Infantry Brigade in de 1st Airlanding Brigade Group, die op zijn beurt onder-deel ging uitmaken van de 1st Airborne Division. In die periode werd ook afgewogen of het Amerikaanse ‘4×4 utility vehicle’, beter bekend als de jeep, geschikt was voor het squadron. De Britten noemde het lichte voertuig al snel de ‘Blitz Buggy’. Om de terreinwagen passend te maken voor vervoer per Horsa-glider wer-den enkele modificaties in het ontwerp doorgevoerd.

Embleem van het Reconnaissance Corps.

In augustus 1942 kwam Major General Browning op bezoek. Hij had zes maroonkleurige (‘bordeauxrode’) baretten onder zijn arm. Hij drukte er één op het hoofd van Gough en gaf hem mee dat vanaf nu andere hoofddeksels verboden waren. In december 1942 kwam het squadron van 1st Airlanding Brigade recht-streeks onder bevel te staan van de divisie.

VERTREK UIT ENGELAND

1st Airborne Reconnaissance Squadron vertrok na een periode van diverse oefeningen op 14 mei 1943 vanuit Liverpool via Gibraltar naar Oran in Algerije voor verdere training. Het squadron kwam daar op 26 mei aan. Op 22 juni kwam 1st Airborne Division onder bevel van 8th Army; het squadron verplaatste daarna deels per glider naar Tunesië. Tot grote teleur-stelling van eenieder nam de eenheid niet deel aan de invasie van Sicilië op 10 juli 1943. Men deed wel bergtraining in het Atlas-gebergte en volgde trainin-gen in parachutespringen.

Twee maanden later werd het squadron wel ingezet bij de operaties in Zuid-Italië; op 9 september werd ontscheept in Taranto en meldde de eenheid zich met zo’n 20 jeeps en 150 man bij 4th Parachute Brigade.

Ze kregen tot taak patrouilles uit te voeren en om vijandelijke bewegingen te melden.

Het dorpje Ruskington, Lincolnshire (Engeland), waar het squadron was gelegerd in Nissenhutten.

Het eerste gebouw rechts was ook in gebruik bij de eenheid (afbeelding van een ansichtkaart uit de jaren ‘30).

Bij één van de D Troop-patrouilles vonden twee man de dood door vijandelijk vuur. In november verhuisde het squadron terug naar Engeland.

Groepsfoto van de officieren van het squadron, genomen in Ruskington, vóór Market Garden. Voorste rij, vijfde van links: Major Gough. Voorste rij, vierde van links: Captain Allsop, plaatsvervanger van Gough. Mid-delste rij, vijfde van links: Lieutenant Bucknall. Middelste rij, zesde en zevende van links: Lt. Christie en Lt.

McNabb. Bovenste rij, vijfde van links: Lt. Pascal. Alle genoemde luitenants zouden de slag om Arnhem niet overleven.

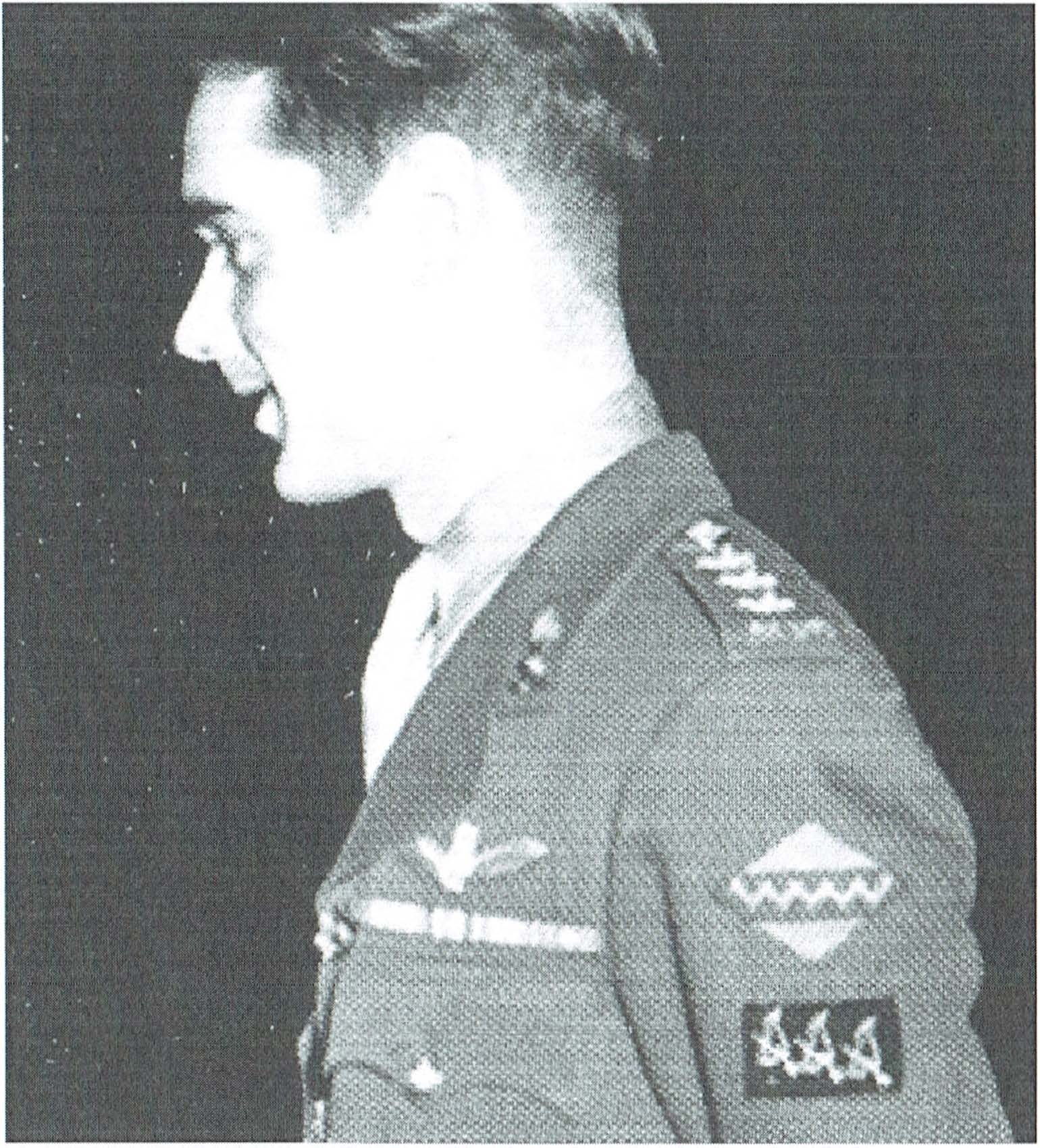

ENGELAND

De eenheid werd gelegerd in Ruskington, Lin-colnshire. De organisatie van het squadron was nog steeds in ontwikkeling en de behoefte aan meer jeeps groeide. In februari 1944 veranderde de tot dan gli-derborne-eenheid in een glider- (de jeeps met hun chauffeurs) én para-eenheid. Het gros van de soldaten moest dus tot parachutist worden opgeleid op RAF Ringway, bij Manchester. De langverwachte jeeps kwamen er ook. In mei 1944 kreeg het merendeel van de 42 terreinwagens K-type Vickers-machine-geweren op aangepaste affuiten. Vlak voor D-Day werd het squadron op ‘72hrs notice to move’ gezet.

Diverse operaties werden gepland en weer afgeblazen.

Medio augustus vertrok het seaborne echelon met elf voertuigen en 25 man naar Normandië. Van operatie Market Garden was nog geen sprake.

Operatie Comet, gepland voor 10 september, werd uiteindelijk ingehaald door operatie Market, waarbij de gehele 1st Allied Airborne Army, dus ook de twee Amerikaanse Airborne-divisies, een rol zou gaan spe-len. Op 12 september om 17.00u deed Major Gene-ral Urquhart zijn bevelsuitgifte aan zijn brigadecom-mandanten. Plek van handeling was Moor Park, het hoofdkwartier van 1st (UK) Airborne Corps. Gough was hierbij aanwezig.

ORGANISATIE VAN HET SQUADRON

De eenheid bestond uit de volgende onderdelen, met tussen haakjes het aantal jeeps dat is ingezet tijdens Market Garden:

• Squadron Headquarters – TAC HQ (twee jeeps en waarschijnlijk enkele motoren); • HQ Troop; • A dministrative Section (drie jeeps). De squa-drondokter, Captain Swinscow, behoorde tot deze groep; • Support Troop, bestaande uit een mortier- en een Polsten gun section tegen luchtdoelen (vier jeeps); • A Troop met een HQ en drie sections (acht jeeps); • C Troop met een HQ en drie sections (acht jeeps); • D Troop met een HQ en drie sections (acht jeeps).

Een troop had naast persoonlijke bewapening een Bren gun, een 2inch-mortier en een PIAT met bijbe-horende munitie. Op de jeeps waren naast radio’s dus ook de genoemde K type Vickers-mitrailleurs gemon-teerd. Ieder sectie had twee jeeps. De sectiecomman-dant was een luitenant, troops hadden een kapitein aan het hoofd staan.

MARKET GARDEN

De opdracht aan 1st Airborne Reconnaissance Squa-dron is hierboven al weergegeven. Gough realiseerde zich snel dat dit een ongebruikelijke wijze van optre-den inhield. In plaats van het uitvoeren van verken-ningen, voor de bataljons uit, kreeg het squadron de taak om een aanval uit te voeren. Bovendien werd deze divisie-eenheid voor de eerste fase onder bevel gesteld van 1st Parachute Brigade. Dit zou nog conse-quenties krijgen. Hij ging in discussie met Brigadier Lathbury. Toen deze niet toegaf, vroeg Gough of hij wellicht Tetrarch Mk VII-tanks kon krijgen, zoals die in Normandië waren ingezet. Uiteindelijk overheerste het gevoel dat de operatie toch een ‘push-over’ zou worden, en was iedereen optimistisch.

Voor deze operatie werden toegevoegd aan het squa-dron: • E en sectie 9th (Airborne) Field Company Royal Engineers, met twee jeep-trailercombinaties; • Een artilleriewaarnemer (één jeep?); • Korporaal Tom Italiaander van No.2 (Dutch) Com-mando Troop – per glider. 22 Horsa-gliders (chalk numbers 354-375) waren bedoeld om 36 jeeps met 75 man te transporteren.

De glider pilots kwamen van C Squadron, The Glider

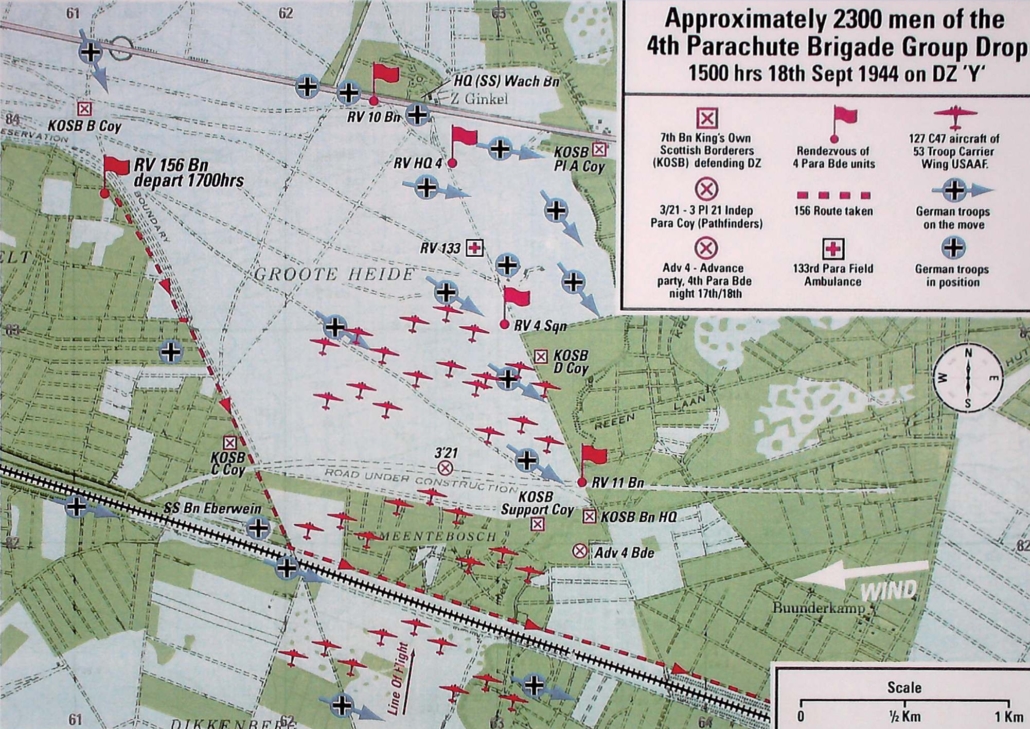

Pilot Regiment. Halifax-vliegtuigen van 298 en 644 Squadron trokken de gliders van RAF Tarrant Rush-ton naar LZ Z bij Wolfheze. De 134 parachutisten van het squadron vertrokken in acht Dakota’s vanaf vliegveld Barkston Heath, vijftien kilometer ten zuid-westen van Ruskington, naar DZ X. Daar zouden zij als laatste, en daarmee als meest noordelijke eenheid, worden gedropt.

Gough vierde op 16 september zijn 43e verjaar-dag. De gliders van Tarrant Rushton vertrokken om 10.20u. De Dakota’s om 11.50u.

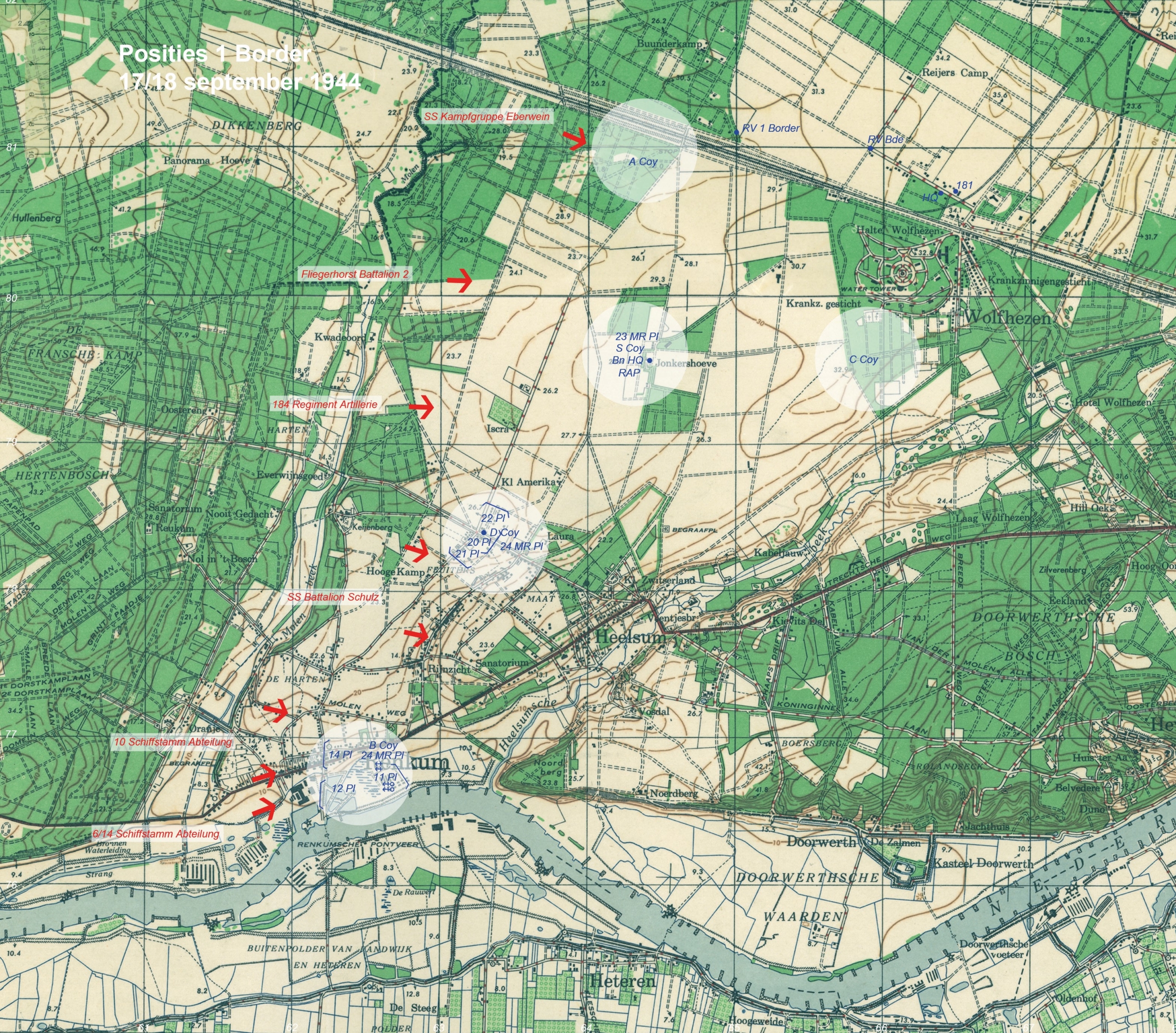

ZONDAG 17 SEPTEMBER

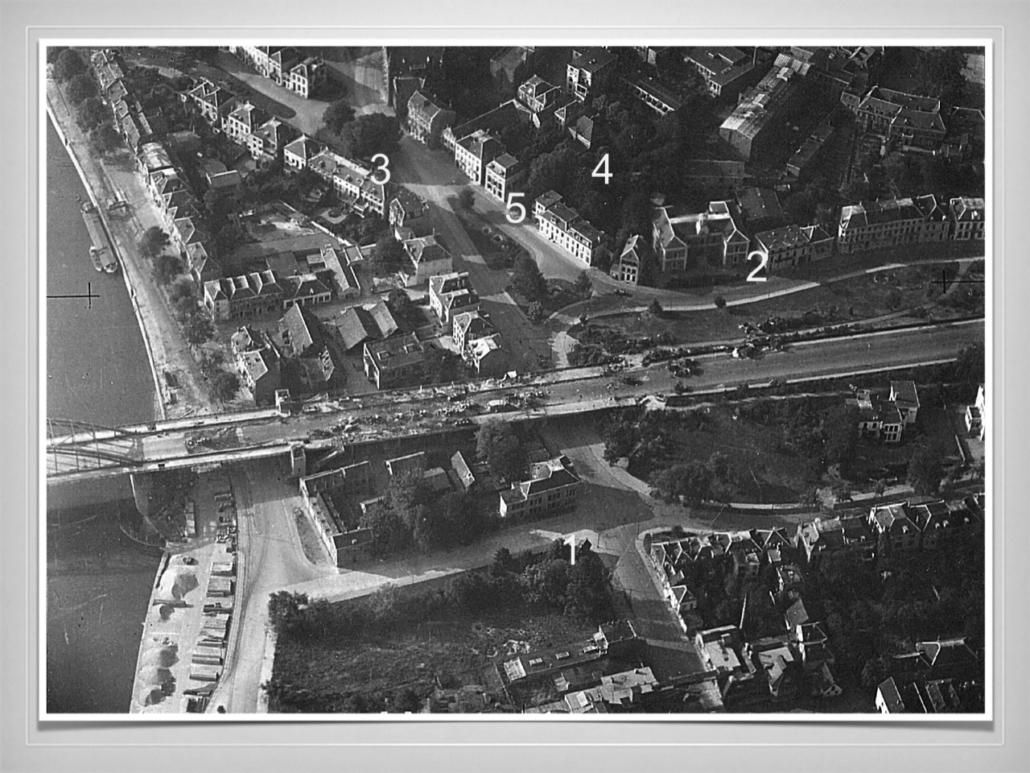

Landing Zone Z was gemarkeerd door No.2 Platoon van de Pathfinders. De markering bevond zich zuid-westelijk van boerderij De Boschhoeve. Om 13.35u begonnen de gliderlandingen van het squadron. Vier Horsa’s van de eenheid crashten tussen de bomen aan de noordkant van de LZ. Dit is op de luchtfo-to’s van 18 september goed te zien. Een Horsa-glider van No.1 Section had een zware landing, waarbij Staff Sergeant Baxter om het leven kwam. De bedoeling was dat de jeeps vanaf LZ Z zouden verplaatsen in westelijke richting, naar de rendez-vous in de bospunt noordelijk van DZ X aan de Telefoonweg. Vanwege de crashes en andere problemen met het uitladen van de zweefvliegtuigen duurde het verzamelen langer dan gepland. In eerste instantie kwamen de jeeps met de genie ook niet aan.

Glider 358 (Recce Squadron HQ) werd bestuurd door Staff Sergeant Jim Wallwork. Glider 359 werd gevlo-gen door Staff Sergeant Oliver Boland. Beide glider pilots hadden deel uitgemaakt van de coup de main force op Pegasus Bridge in Normandië. Ook toen was RAF Tarrant Rushton het vertrekpunt. Beide gliders kwamen zonder problemen aan op LZ Z. Om 14.08u werden de parachutisten van het squadron gedropt op de met blauwe rook gemarkeerde DZ X. De drop ver-liep beter dan tijdens menig training in Engeland.

Vanwege de diverse crashes ontstond het gerucht dat de coup de main mislukt was. Het hielp ook niet mee dat de liaison officer (LO), Captain Poole, zich niet had gemeld bij Lathbury. Het was vooral A Troop van Captain Grubb die problemen had met uitladen; nog een geluk dat deze eenheid was aangewezen als divi-siereserve en dus geen taak had bij de initiële aanval.

Van de 36 jeeps waren 28 ingedeeld voor de coup de main. Slechts 25 waren uiteindelijk beschikbaar.

De locatie waar C Troop met de haastig ingerichte verdediging van SS-Panzergrenadier-Ausbildungs- und Ersatz-Abteilung 16 van Krafft in gevecht raakte. De coup de main werd hier al in een vroeg stadium in de kiem gesmoord (foto uit 1946 of 1947).

Om 15.40u gaf Gough het startsein voor vertrek.

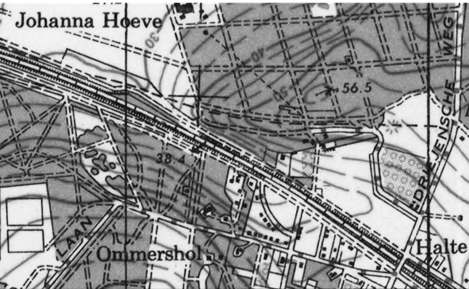

C Troop was de spits, gevolgd door Tactical HQ, D Troop, Support Troop en de rest van HQ Troop. De bedoeling was dat C Troop voorop zou gaan met 9 Section gevolgd door 7 en 8 Section. Vanwege de late aankomst van de jeeps bij de RV werd Lieute-nant Bucknall, sectiecommandant van No.8 Secti-on, ongeduldig. Hij wachtte niet op zijn eigen radio-dragende jeep, maar vertrok met nog drie man in het tweede voertuig zonder radio. Terwijl hij op de Tele-foonweg reed, in de bocht bij de spoorwegovergang, arriveerde de radiodragende jeep met nog eens vijf man, waarover Lance Sergeant McGregor het commando voerde. De zes volgden Bucknall. No.8 Section haalde No.9 Section in. Dit hoorde bij de (overlappende) procedure. Ten noorden van de spoorweg reed No.8 Section nu als spits over de Johannahoeveweg.

Nadat Bucknall het tunneltje onder de spoorweg was gepasseerd reed hij om 15.50u de (nu verdwenen) heu-vel op. Op dit punt hadden de Duitsers van SS-Pan-zergrenadier-Ausbildings- und Ersatz-Bataillon 16 van Sturmbannführer (majoor) Krafft een haastige verde-diging ingericht. In tegenstelling tot wat vaak wordt beweerd was hier dus geen sprake van een hinderlaag, maar van een ontmoetingsgevecht. Te midden van de Duitse verdediging werd de jeep beschoten, waar-bij alle inzittenden omkwamen. Secties 9 en 7 pro-beren het gevecht te beïnvloeden door te steunen en te omtrekken. Het gevecht duurde echter tot 18.30u, waarbij zeven man sneuvelden en meerdere gewond raakten. Vier Recce-mannen werden krijgsgevangen gemaakt.

Om 16.45u kreeg Major Gough bericht dat de di-visiecommandant hem zocht. Ook Urquhart had het gerucht bereikt dat de meeste voertuigen van het squadron niet waren aangekomen. Urquhart bezocht het HQ van 1st Airlanding Brigade, maar de com-mandant, Brigadier Hicks, was zelf niet aanwezig. Nu al speelden verbindingsproblemen op. Urquhart liet weten dat Gough hem moest proberen te bereiken bij de HQ van 1st Parachute Brigade. Deze volgde echter 2nd Battalion op weg naar de brug. De divisiecom-mandant ging alleen (!) met zijn verbindingsman in de jeep op pad. Met zijn Wireless Set No.22 tracht-te hij Gough te bereiken. Laatstgenoemde luisterde echter niet in op het commandonet van de divisie, maar was ingeplugd op dat van 1st Parachute Brigade.

Nadat Gough had begrepen dat Urquhart hem zocht, reed hij naar de divisiecommandopost op LZ Z. Daar ruilde hij zijn twee squadronjeeps om en vertrok hij meteen om de divisiecommandant in te halen, via de meest waarschijnlijke route. Gough kwam zo als enige, met twee jeeps en later een motorfiets, bij het aanvalsdoel van het squadron uit: de brug in Arnhem.

Urquhart bevond zich echter met Lathbury bij 3rd Parachute Battalion op de Tiger-route, ter hoogte van de Bilderberg, westelijk van Oosterbeek.

Inmiddels had Captain Allsop als plaatsvervangend commandant de leiding van het squadron overgeno-men. Hij meldde zich bij Hicks en kreeg te horen dat hij één troop bij 1st Airlanding Brigade moest ach-terlaten. Effectief had Allsop dus nog maar één troop over, omdat A Troop reeds onder direct bevel stond van de divisie. Aan het einde van de dag waren A, C en D Troop verzameld rondom Divisional HQ op LZ Z. Er was dus geen plan B voor het geval de coup de main zou mislukken. 1st Airborne Reconnaissan-ce Squadron stond weer onder bevel van de divisie.

Opdrachten kwamen van general staff officer (GSO 1 – Operations) Lt. Col. McKenzie.

MAANDAG 18 SEPTEMBER

Om 06.30u kreeg het squadron, minus C Troop, op-dracht om vanuit Heelsum in de richting van Arnhem te verkennen. Dat verliep goed tot Mariëndaal. In de buurt van het viaduct bij KEMA werd D Troop onder vuur genomen door minstens vier machinegeweren

(deze naderingsmars over de Utrechtseweg is gefilmd, waarbij ook de door het squadron gevoerde Polsten guns, luchtdoelgeschut, zichtbaar is (zie hiervoor You-Tube, zoekwoorden ‘home movie Monné family’).

Een aantal uur eerder was op deze zelfde locatie 1st Parachute Battalion in gevecht geweest, voordat het over de Lion-route uiteindelijk richting Arnhem op-trok, en even daarna had 3rd Battalion er direct con-tact met de vijand. Na het vuurgevecht bij Mariën-daal verzamelde het squadron zich in de Backerstraat, waar ze last ondervonden van infiltrerende SS’ers. Tac HQ werd ingericht nabij kasteel Sonnenberg, noord-westelijk van Hartenstein. D Troop werd uiteindelijk afgelost door 2nd Battalion, South Staffordshire Re-giment. De achtergelaten C Troop bewaakte intussen de oostelijke flank, ten noorden van de spoorweg, en bereikte de plek waar Peter Bucknall was gesneuveld.

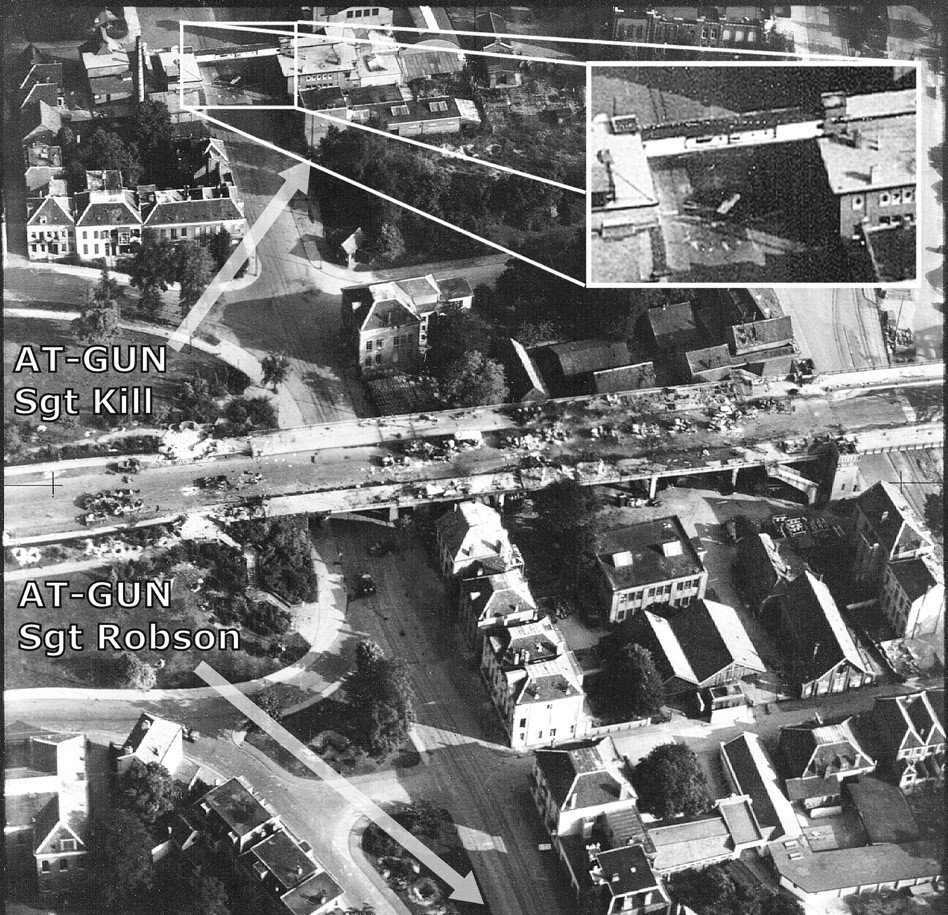

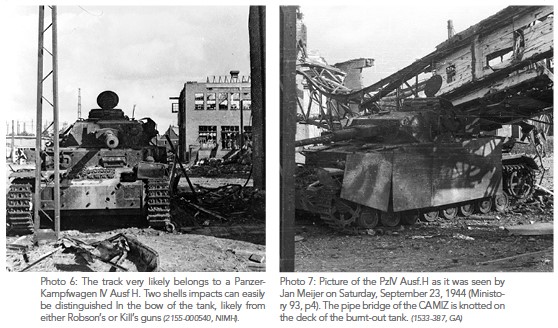

A Troop bevond zich nu in Oosterbeek. Bij de brug in Arnhem leverden de twaalf man van het squadron hun bijdrage aan het gevecht met de eenheid van Hauptsturmführer Gräbner die vanuit het zuiden de brug aanviel. Opvallend is dat Gough Trooper White opdroeg op de motor een bericht naar Divisional HQ te brengen, wat nog lukte ook. Zij het dat de motor daarbij verloren ging.

De tweede Britse airlift bracht ook twee Horsa-gli-ders met drie voertuigen en twee motoren voor Recce Squadron. ‘s Avonds bevond het squadron zich in de buurt van Oranjestraat en kasteel Sonnenberg in Oosterbeek.

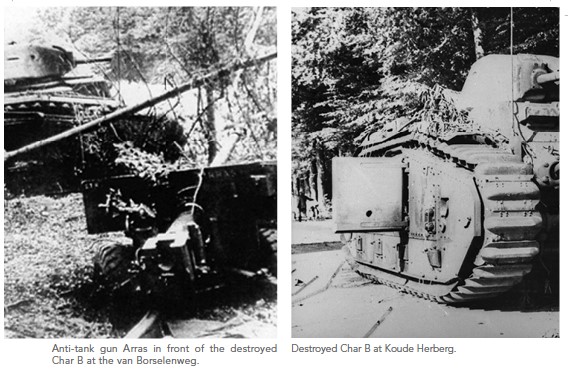

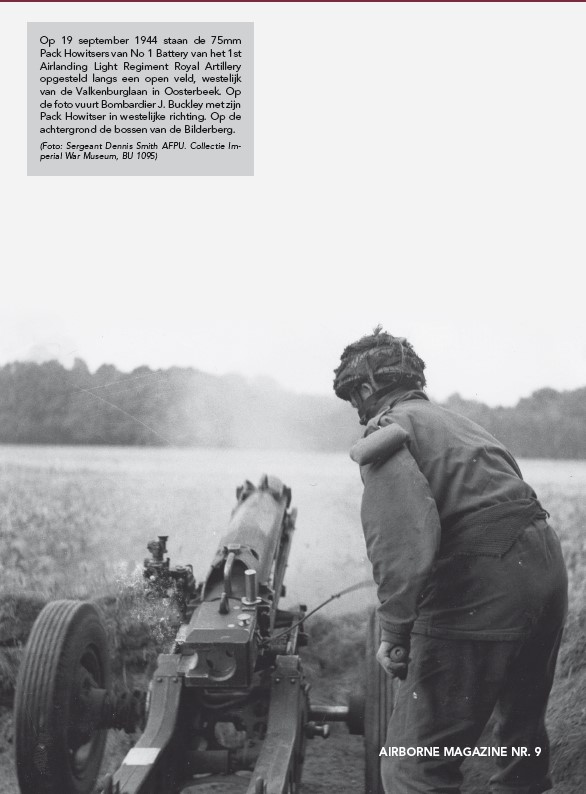

DINSDAG 19 SEPTEMBER

Terwijl in Arnhem de gevechten bij het St. Elisabeth Gasthuis en Museum Arnhem gaande waren, kreeg het squadron van vervangend divisiecommandant Hicks de opdracht in westelijke richting (Heelsum) te verkennen. Een eerste indicatie dat Duitse troepen vanuit het westen richting Oosterbeek verplaatsten, kwam van een RASC-eenheid die bezig was voorra-den van een dump bij Wolfheze naar Oosterbeek te brengen. In de bossen ten noorden van kasteel Door-werth kwam een sectie van D Troop in gevechtscon-tact. A Troop meende in de buurt van Heelsum zelfs een Char B-tank te hebben gezien. Ter hoogte van het kruispunt Wolfhezerweg-Utrechtseweg, waar het tactisch hoofdkwartier van het squadron was ingericht werden de twee Polsten guns in stelling gebracht.

Eén van de uitgeschakelde jeeps van C Troop (bron: IWM).

De zwaarste gevechtsactie vond plaats bij de reeds gesleten C Troop. Na de vorige dag in reserve te zijn geweest ging C Troop na een goed ontbijt op weg naar de Amsterdamseweg, ten noorden van Wolfheze.

Bij de kruising waar tegenwoordig een ANWB-we-genwachtstation is gevestigd kwam C Troop onder Duits mortiervuur te liggen. De eenheid trok daar-op terug op Wolfheze. Hierbij ging een jeep van C Troop verloren. Vervolgens werd verkend over LZ S nabij Buunderkamp. Daar naderden ze wederom de Amsterdamseweg bij Planken Wambuis. Tussen 12.00u en 15.30u namen ze Duitse troepen waar.

Om 15.30u werd een herbevoorrading gedropt. De terugtochtroute bleek afgesneden. Toen het Duitse luchtafweer begon te schieten op de vliegtuigen van de derde Britse air lift besloot de C Troop-comman-dant, Captain Hay, met alle zes jeeps op hoge snelheid uit te breken over de weg van Planken Wambuis richting Wolfheze. Van de vier jeeps die in de hinderlaag reden, was er slechts één die erdoor wist te komen.

De twee laatste jeeps vermeden de hinderlaag, maar één werd door de Duitsers alsnog uitgeschakeld. De

bemanning werd krijgsgevangen gemaakt. Uiteinde-lijk keerden twee jeeps en zeven overlevenden terug bij het squadron in het verzamelgebied bij de Koude Herberg-Oranjelaan. C Troop was vertrokken met 38 man. Slechts zeven man waren nu nog inzetbaar. De rest was gedood of krijgsgevangen gemaakt.

Diezelfde middag moest de eenheid twee jeeps leveren om de inmiddels van de schuilplaats op de Zwarte-weg teruggekeerde Urquhart te escorteren naar het hoofdkwartier van 4th Parachute Brigade die bij Jo-hannahoeve in de knel was gekomen. A Troop was in actie tussen station Oosterbeek en station Wolfheze.

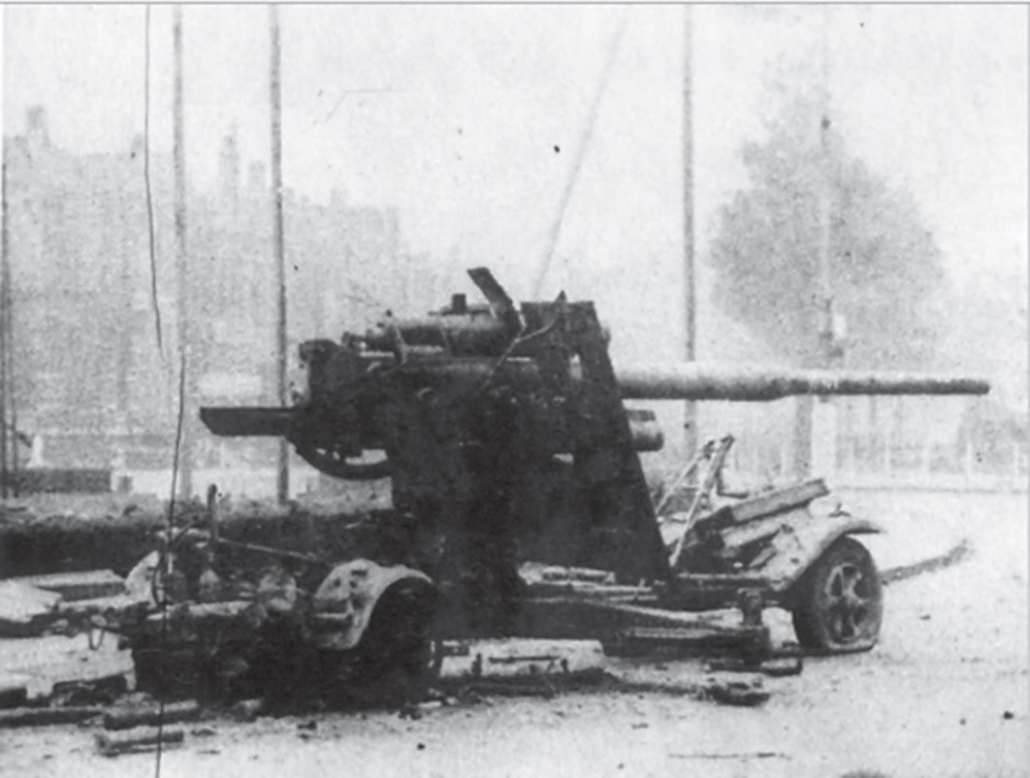

D Troop deed verkenningen tussen de Lebretweg en de spoorweg Arnhem-Nijmegen. Voor deze opdracht was de troop tijdelijk versterkt met een 6ponder-anti-tankkanon. Aan het eind van de dag werden de troops teruggehaald naar het verzamelgebied dat intussen ten noorden van Hartenstein lag. De Polsten Section nam stellingen in bij het kruispunt waaraan Hotel Schoon-oord en Hotel Vreewijk lagen. In de duisternis reed hier een jeep tegen een Polsten gun, waarbij de loop gebogen raakte. Bij de brug in Arnhem had Gough inmiddels het commando over 2nd Parachute Battalion overgenomen omdat ook de plaatsvervangend commandant, Major Tatham Warter, gewond was ge-raakt. Lieutenant Colonel Frost trad op als plaatsver-vangend commandant van 1st Parachute Brigade, in afwezigheid van Lathbury.

WOENSDAG 20 SEPTEMBER

De dag dat de brug bij Nijmegen in geallieerde han-den viel was er een van hevige strijd in Oosterbeek.

Tot dan had 1st Airborne Reconnaissance Squadron zich nog verdienstelijk kunnen maken met jeepver-kenningen, maar vanaf woensdag restte alleen nog een verdedigende taak. A Troop kreeg waarnemingsop-drachten rondom de Stationsweg, D Troop rondom de Dennenkampbossage. Daar kregen de troops te maken met zware artillerie- en mortierbeschietingen.

A en D Troop kregen ’s avonds opdracht langs de Paul Krugerstraat een aantal huizen ter verdediging in te richten. Squadron Tac HQ bevond zich bij de Oran-jeweg. De Support Troop, onder commando van Lui-tenant John Christie, kreeg opdracht de twee Polsten guns bij Schoonoord en Vreewijk in te zetten tegen Duits gemechaniseerd geschut. Zonder eerst een ver-kenning te doen reed Christie naar de stelling. Daar kwamen de twee jeeps onder kleinkalibervuur te lig-gen en iedereen zocht dekking. Toen de luitenant zelf probeerde de jeep in een gedekte opstelling te krijgen, werd hij in zijn borst getroffen door een granaat. Hij wist nog naar zijn mannen te lopen, maar viel daar dood neer. Dit gebeurde recht tegenover Klein Har-tenstein, bij Villa Eureka. Diezelfde dag gingen nog twee jeeps van het squadron verloren.

Bij de Arnhemse verkeersbrug trad Gough inmiddels op als deputy force commander, nadat Frost gewond was geraakt door de inslag van een mortiergranaat.

Belangrijke beslissingen namen de heren in overleg.

Het einde bij de brug naderde echter snel. Er werd een staakt het vuren geregeld om de gewonden over te dragen aan de Duitsers.

DONDERDAG 21 SEPTEMBER

De dag begon weer vroeg met Duitse beschietingen.

De Westerbouwing ging deze donderdag verloren en de Duitsers namen de brug bij Arnhem in, nadat de troepen van Frost zich hadden overgegeven. XXX Corps trok vanuit Nijmegen de Betuwe in. Op het

einde van de dag landden er 1.000 Polen op DZ K bij Driel. A en D Troop waren nog steeds in hun stel-lingen aan de Paul Krugerstraat. A Troop had zijn tactisch hoofdkwartier in de bakkerij van Crum, op de kruising met de Mariaweg. Daar begon in de mid-dag een Duits gemechaniseerd geschut huizen op te blazen. Trooper Frank Mann wist vanuit de bakkerij met een PIAT dit Sturmgeschütz te immobiliseren.

Hiervoor werd hij later onderscheiden met het Ame-rikaanse Distinguished Service Cross. Na deze actie wisten de Duitsers de bakkerij (Paul Krugerstraat 23) in te nemen. Omdat hiermee de stellingen van de Britten in direct gevaar kwamen, leidde de comman-dant van A Troop, Captain Grubb, een tegenaanval om de Duitsers te verdrijven. Niet veel later voerden de Duitsers een goed gecoördineerde aanval uit op de stellingen van D Troop aan de Steijnweg, in de buurt van huisnummer 45. No.10 Section kreeg het zwaar te verduren. Er vielen gewonden. De sectiecomman-dant, Lieutenant Marshall verloor zijn rechterhand.

Nadat deze sectie was uitgeschakeld, viel de beurt aan No.11 Section van Lieutenant Hodge. Uiteindelijk bleven nog maar zo’n twintig man over in D Troop, voornamelijk van No.12 Section.

Uitgeschakelde jeep van Support Troop. De foto is genomen tegenover Klein Hartenstein. Villa Eureka op de achtergrond staat er nog steeds. (bron: BArch-MA Freiburg).

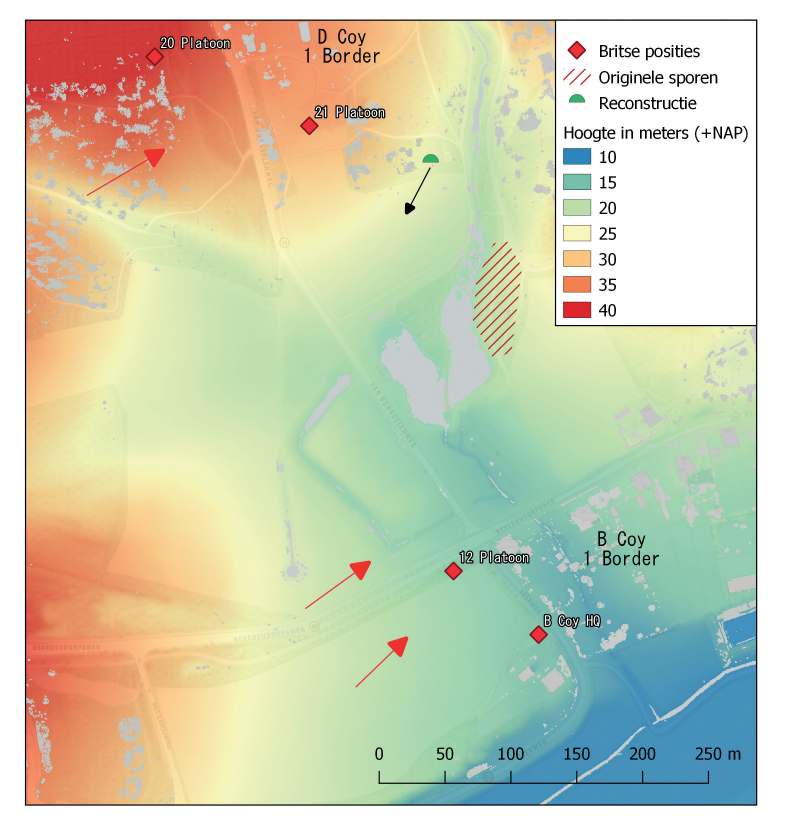

VRIJDAG 22 SEPTEMBER

Op deze dag kwam de artillerie van 2nd Army ter beschikking. Er was radiocontact met het 64th Me-dium Regiment RA in Nijmegen. Deze eenheid kon met zware artillerie Duitse troepenconcentraties rond de perimeter beschieten. De Duitsers bestookten op hun beurt de Britten met hun ‘morning hate’. Eén van deze mortierbeschietingen schakelde de twee 81mm-mortieren van Support Troop uit. Waarschijn-lijk waren die opgesteld in de buurt van het hoofd-kwartier van 1st Battalion, The Border Regiment.

Hierbij kwam Corporal Mason om en raakten twee anderen gewond. Het resterende deel van de Polsten Section bevond zich ook bij Squadron HQ. Er von-den infiltraties door Duitsers plaats en voedsel en wa-ter werden een probleem. Ook het in werking houden van de batterijen werd een uitdaging. Bij Squadron HQ, in een bossage net westelijk van het huidige Airborne-monument tegenover Hartenstein, bevond zich een batterij-oplaadapparaat. Het werkte, maar ondervond veel problemen.

De Nederlandse commando Tom Italiaander, verbon-den aan het squadron, had veel geluk. Bij een mortier-beschieting sprong hij in een schuttersputje, waarin een moment later een mortiergranaat landde die niet explodeerde. Ook de squadron dokter Swinscow had een dergelijke ‘narrow escape’.

ZATERDAG 23 T/M 26 SEPTEMBER

Op zaterdagochtend kreeg D Troop het in de om-geving van Oranjeweg-Bothaweg-Steijnweg zwaar te verduren. Na de gebruikelijke ochtendbeschie-ting vielen de Duitsers aan, hierbij ondersteund door pantservoertuigen. De enige 6-ponder in die omgeving werd uitgeschakeld, waarbij de bediening sneuvelde. Bij de kruising van de Steijnweg en Paul Krugerstraat, waar zich ook het hoofdkwartier van D Troop bevond, werd hard gevochten. Sergeant Pyper werd hiervoor met een Military Medal beloond. ‘s Middags werd A Troop uit de huizen ten zuiden van de Paul Krugerstraat verdreven en namen zij nieuwe posities in aan de De la Reyweg. Bij deze gevechten raakte troop commander Captain Grubb gewond aan zijn voet. Nadat hij werd afgevoerd naar de verband-post nam Lieutenant Galbraith (No.2 Section) het commando over. Overigens bevonden de jeeps zich nog steeds bij de troops, veelal geparkeerd achter de huizen. Maar vanwege de intensieve mortierbeschietingen gingen ook deze één voor één verloren.

De mannen vochten niet alleen in de huizen maar groeven ook schuttersputten in de tuinen. D Troop startte de operatie met 48 man. Hiervan konden nu nog maar twaalf actief strijd leveren.

Op zondagochtend werd D Troop nog eens zwaar ge-troffen. Na een extra zware mortierbeschieting wer-den troop commander Captain Park, No.12 Section commander Lieutenant Pascal en Trooper Walker ge-dood, terwijl ze in hun loopgraaf stonden. Kort daar-op overliepen de Duitsers de positie van D Troop, waarmee deze troop ophield te bestaan.

Het was ook op deze zondag dat Colonel Graeme Warrack als divisie-arts vroeg om een staakt-het-vu-ren om de gewonden af te kunnen voeren naar het St. Elisabeth Gasthuis. Op maandagavond 25 september

In de laatste dagen van de slag lag het operatiege-bied van het squadron in de wijk ten noorden van Hartenstein: tussen de Oranjeweg, Paul Kruger-straat en Mariaweg

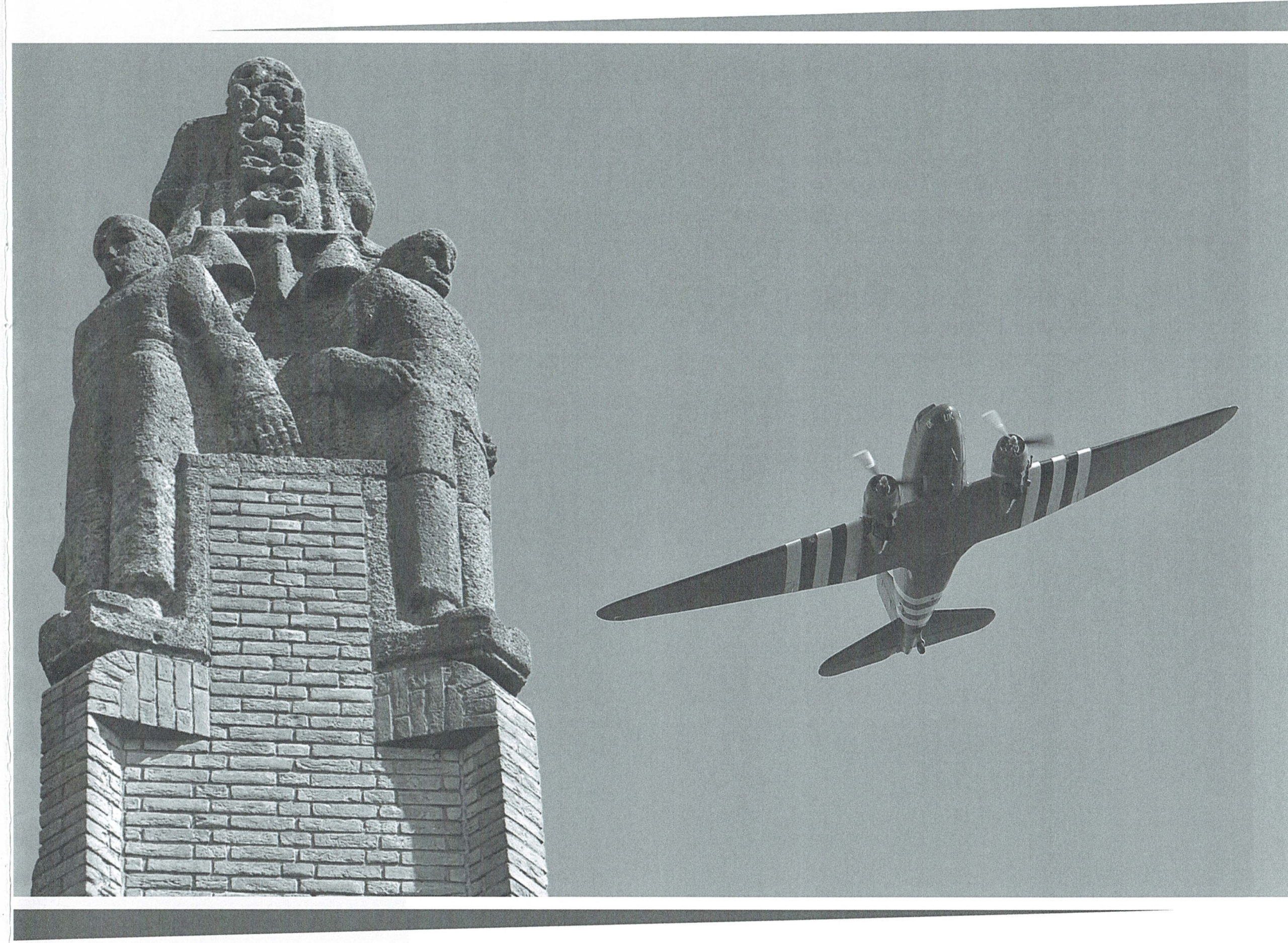

kreeg het Squadron om 19.30u opdracht hun posities te verlaten en te evacueren over de Nederrijn. De start was om 20.50u. De troopers vertrokken in paren. De route was gemarkeerd met witte linten. De route liep via de Hoofdlaan over de Benedendorpsweg en door wat nu bungalowwijk Dennenoord is naar de uiter-waarden bij de Nederrijn. Canadese genisten brach-ten de meesten over rivier.

Na een kort verblijf in Nijmegen werd het squadron via Brussel teruggevlogen naar Engeland, waar het op 29 september 1944 aankwam op vliegveld RAF Saltby. De mannen werden teruggebracht naar Rus-kington. Op 17 september was het squadron met tien vrachtwagens naar het vliegveld gebracht. Nu waren er slechts twee vrachtwagens nodig om hen naar hun legering te brengen. Er volgde een emotioneel ont-vangst door de inwoners van Ruskington in squadron pub The Shoulder of Mutton. De troopers kregen twee weken verlof. Na terugkeer werd het squadron gereorganiseerd met Captain, en wat later Major Allsop als commandant.

Van de 25 officieren vonden zeven de dood. Van de om en nabij 184 manschappen overleefden er 23 de slag niet. De anderen, waarvan de meesten gewond, werden merendeels krijgsgevangen gemaakt; slechts enkele tientallen keerden terug over de Nederrijn.

De gewonde krijgsgevangenen werden in eerste in-stantie ondergebracht in de Willem III-kazerne in Apeldoorn. Slechts een enkeling wist te ontsnappen en dook onder. In Brummen had Gough een close call toen Majors Hibbert en Mumsford ontsnap-ten door uit een vrachtwagen te springen: een SS’er schoot uit frustratie in de vrachtwagen en doodde en verwondde een aantal van de krijgsgevangenen. De gewonde Lieutenant McNabb, de inlichtingenofficier van het squadron, overleed later aan de gevolgen van deze misdaad.

– Erik Jellema

BELANGRIJKSTE BRON

Robert (Bob) Hiltons Freddie Gough’s Specials at Arnhem.

De voornaamste bron voor dit artikel en de battlefield tour is het boek Freddie Gough’s Specials at Arnhem, Robert (Bob) Hilton (2017), een prachtig geïllus-treerde uitgave van R.N. Sigmond Publishing. Bob (58) vocht als parachutist in de Falkland-oorlog van 1982. In 2000 werd hij custodian van de 1st Airborne Reconnaissance Squadron history, van 2014 tot 2017 was hij assistent-curator van het Airborne Assault Museum in Duxford (Engeland). Bob woont in Ne-derland en leidt vaak battlefield tours.

OVERIGE BRONNEN

• Remember Arnhem, John Fairley (1978). • Roll of Honour, Battle of Arnhem September 1944 (revisie 5, 2011).

Volgend jaar organiseert de VVAM de battlefield tour ‘1st Airborne Reconnaissance Squadron tijdens de slag om Arnhem’. Luuk Buist en Erik Jellema zullen de gid-sen zijn. Aanmelden voor deze battlefield tour kan te zijner tijd op de website van de Vereniging Vrienden van het Airborne Museum.

DE COMMANDOVOERING VAN 3RD PARACHUTE BATTALION OP DE FALKLANDS EN IN ARNHEM

“THEY DON’T NEED BRIEFING, JUST TELL THEM THAT’S THE BLOODY WAY”

Op 21 september leidden Erik Jellema en ik een gezelschap van Falkland-veteranen rond langs de opmarsroute van hun voorgangers tijdens de slag om Arnhem. Een speciale tour, niet alleen omdat het gezelschap bestond uit mannen van A Company, 3rd Parachute Bat-talion, maar ook omdat Erik en ik in 2002 de voormalige Falkland-slagvelden bezochten.

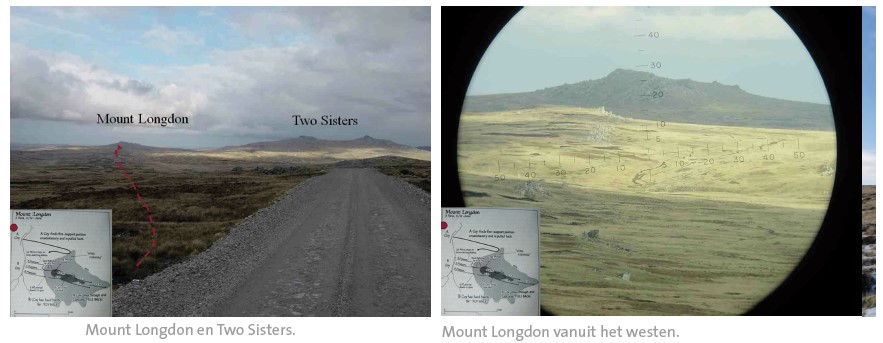

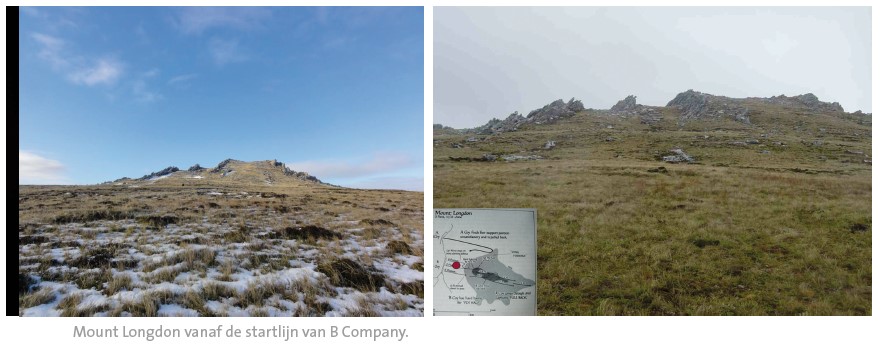

Daar ervoeren we met welke uitdagingen dit bataljon in juni 1982 was geconfronteerd toen zij de opdracht kregen om Mount Longdon te heroveren op de Argentijnen. Het con-trast met de commandovoering in Arnhem had niet groter kunnen zijn.

MOUNT LONGDON (1982)

De strijd om de herovering van de Falkland-eilanden op de Argentijnse bezetting was ruim een maand on-derweg toen de Britten zich in de tweede week van

Veteranen van A Company bij het Airborne-monument in Heelsum.

juni 1982 opmaakten voor de aanval op de strategische havenstad Stanley op East Falkland. Voor een goede uitgangspositie tijdens deze laatste fase van het conflict was het noodzakelijk eerst een reeks, door de Argentijnen ingenomen heuvels ten westen van de stad te zuiveren. Omdat met een eerdere Argentijnse Exocet-aanval op het vrachtschip Atlantic Conveyor de Britse helikoptercapaciteit verloren was gegaan, waren de bataljons van 3 Commando Brigade gedwongen de 65 kilometer van hun landingsplaats in San Carlos Bay naar deze hoogten te voet af te leggen. Een enorme op-gave vanwege het ontbreken van een goed wegennet en de invallende winter in de South Atlantic.

De slag om Stanley

De Engelse commandant van 3 Commando voorzag een aanval in drie fasen. In fase 1 zouden drie bataljons, 3rd Parachute Battalion en 45 & 42 Commando Royal Marines tegelijkertijd Mount Longdon, Two Sisters en Mount Harriet aanvallen. In fase 2 zou de 5th Infantry Brigade met 2 Para en het 2nd Battalion Scots Guards ‘s nachts Wireless Ridge en Tumbledown Mountain innemen. De 7th Gurkha Rifles zouden bij vroegtijdig succes van de Schotten doorstoten naar Mount Wil-liam. Fase 3 zou later in detail worden uitgevoerd; re-kening werd gehouden met straatgevechten in Stanley.

De Argentijnse verdediging op Mount Longdon werd gevormd door B-compagnie van Regimiento de Infan-tería Mecanizado 7. De aandacht van de drie infan-teriepelotons was met prioriteit naar het noorden en westen gericht. Nadat 3 Para na drie dagen van ver-plaatsingen te voet was aangekomen in de buurt van Estancia House, liet de commandant, Lieutenant Co-lonel Hew Pike, verkenningspatrouilles uitvoeren in de richting van zijn aanvalsdoel: Mount Longdon.

De opmars over East Falkland.

EEN KANSLOOS PLAN

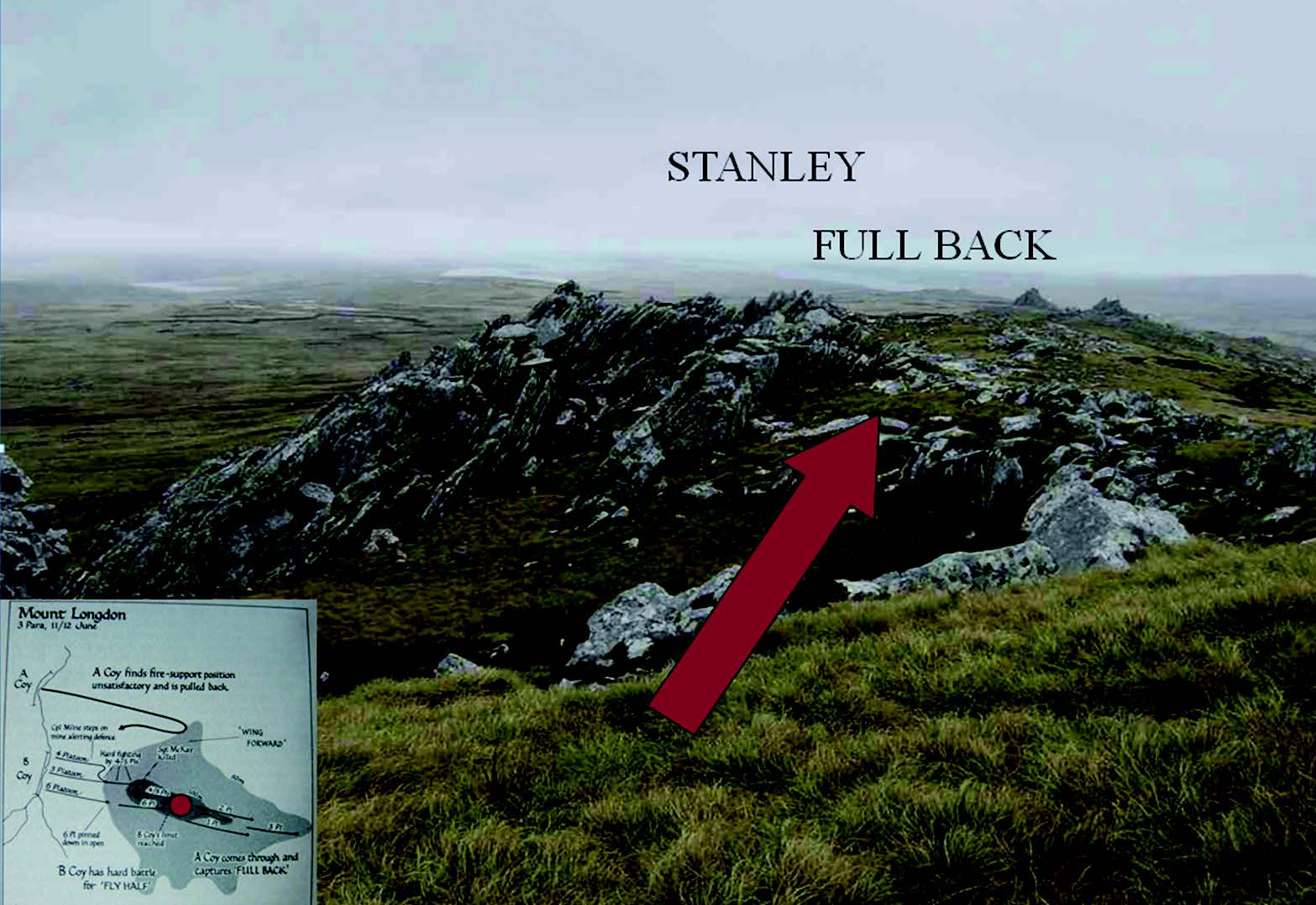

Tijdens ons bezoek aan de eilanden in 2002 werden wij rondgeleid door een gids die in 1982 als Lance Corporal had deelgenomen aan verkenningspatrouil-les op de berg. Hij vertelde dat zijn patrouille erin was geslaagd via de zuidzijde tot vlak onder de top te ko-men. Daarbij hadden ze vastgesteld dat de Argentijn-se posten lagen te slapen. Ondanks de hoopgevende verkenningsresultaten besloot de bataljonscomman-dant bij het opstellen van zijn aanvalsplan niet via de zuidkant te gaan. In zijn ogen was een nadering van-uit deze richting niet mogelijk vanwege de mogelijke aanwezigheid van mijnenvelden. Pike koos uiteindelijk voor een frontale aanval vanuit het westen. Opvallen-de terreinkenmerken had hij codenamen gegeven. Een beheersende heuvel ten noorden van Mount Longdon kreeg de codenaam Wing Forward. De meest westelijke top noemde hij Fly Half en de meeste oostelijke Full Back. In het plan van de bataljonscommandant kreeg A Company de opdracht Wing Forward te veroveren.

Van daaruit zouden zij B Company steunen, in eerste instantie bij het innemen van aanvalsdoel Fly Half, en vervolgens Full Back. C Company werd als bataljons-reserve achter de hand gehouden. D Company had de opdracht de startlijn te verkennen en de route erheen van gidsen te voorzien.

Van daaruit zouden zij B Company steunen, in eerste instantie bij het innemen van aanvalsdoel Fly Half, en vervolgens Full Back. C Company werd als bataljons-reserve achter de hand gehouden. D Company had de opdracht de startlijn te verkennen en de route erheen van gidsen te voorzien.

Op 11 juni startte 3 Para na het invallen van de duister-nis met de naderingsmars tot de startlijn tien kilometer verderop. Het uur U was 20.00u. Pike had besloten tot een stille nachtaanval en zag af van inleidende be-schietingen door de artillerie. Terwijl B Company in verspreide formatie voorzichtig voorwaarts ging over de startlijn, stapte één van de soldaten op een mijn.

Vanaf dat moment was het verrassingselement weg en waren de Argentijnen gealarmeerd. Ze openden het vuur met alles wat ze hadden. Terwijl B Company in gevecht was, naderde A Company de opstellingen op Wing Forward. Ter plekke bleek dit een verre van ide-ale opstelling te zijn. Wing Forward lag veel lager dan de toppen van Longdon. Daarnaast bleek het zwaarte-punt van de Argentijnse opstellingen gericht te zijn te-gen een nadering vanuit het noorden. Vanuit de hoger gelegen opstellingen op Mount Longdon keken de Ar-gentijnen op A Company neer en kon men vanuit hun verdedigende opstellingen effectief vuur uitbrengen.

Pike zou de compagniescommandant van A Company, Major Collet, vervolgens hebben opgedragen Mount Longdon vanuit Wing Forward aan te vallen, om de inmiddels zware verliezen leidende B Company te steu-nen. Major Collet beschouwde deze opdracht echter als onrealistisch. In zijn ogen zou zo’n aanval tot zwa-re verliezen onder zijn compagnie hebben geleid. Hij deed alsof hij geen radioverbinding meer had met zijn bataljonscommandant en keerde terug naar de startlijn om zijn compagnie van daaruit achter B Company aan te laten oprukken naar het hoger gelegen Fly Half.

Van daaruit zou hij B Company voorwaarts kunnen doorschrijden om zo de aanval van deze eenheid over te kunnen nemen naar Full Back. De officiële versie in de verslagen die in diverse boeken hierover is opge-nomen vermeldt dat Pike Collet opdracht gaf terug te trekken en zich achter B Company op te stellen. Uit de gesprekken met de veteranen tijdens de battlefield tour in Arnhem bleek echter dat Collet deze opdracht heeft geweigerd en zelf tot de terugtrekking had besloten.

ZWARE VERLIEZEN

Inmiddels waren de pelotons van B Company tussen de rotsformaties op de westelijke zijde van de heuvel aangekomen. Zij waren door de rotsspleten gekanali-seerd en konden nauwelijks manoeuvreren. Hierdoor waren ze kwetsbaar voor Argentijns vuur en voor de vij-andelijke handgranaten. Deze worden vanaf de hoger gelegen opstellingen in de rotsspleten gegooid waardoor de Britten deze plek later hebben omgedoopt tot Grenade Alley. In een urenlang gevecht van man tegen man kwam B Company maar moeilijk verder. Uiteindelijk slaagde Lieutenant Bickerdike van 4 Platoon erin om op de linkerflank, via de rotsspleten, door te stoten.

Nadat zij enkele mitrailleurposten hadden uitgescha-keld, raakte hij gewond door een kogel in zijn zij. Hij riep Platoon Sergeant Ian McKay bij zich en droeg het peloton aan hem over. Corporal Bailey, één van de sec-tiecommandanten in 4 Platoon, beschrijft wat er toen gebeurde: “Ian and I had a chat and decided the aim was to get across to the next cover. There were some Argentinian positions but we didn’t know the exact location. He shouted out to the other corporals to give covering fire. Three machine guns altogether sergeant McKay, myself and three privates set off. As we were across the open ground two of the privates were killed. We grenaded the first position and went past it without stopping, just firing into it. And that is when I got shot. I got it in the hip and went down.

McKay was still going on the next position, but there was no one else with him. The last I saw of him was he was just going on. I was lying on my back and listened. The lads were calling out to McKay, there was no reply. I got shot again soon after, by bullets in the neck and hand.” McKay slaagde erin om ook deze mitrailleurspost uit te schakelen, maar sneuvelde daarbij. Zijn kameraden troffen het lichaam van McKay aan op de uitgeschakel-de Argentijnse opstelling. Voor deze actie werd McKay postuum onderscheiden met het Victoria Cross.

ONGEHOORZAAMHEID

Met zware verliezen slaagde B Company er uiteinde-lijk in de eerste hogergelegen top ter hoogte van Fly Half te bereiken. De compagnie had dan al tien dode-lijke slachtoffers te betreuren. Met de gewonden erbij verloor de eenheid de helft van zijn sterkte. Omdat de compagnie niet sterk genoeg was de aanval verder voort te zetten naar Full Back, werd besloten A Company het gevecht van B over te laten nemen. In tegenstelling tot het eerste deel van de aanval kon de vervolgaanval nu wel met artillerie worden ondersteund. Een vuurba-sis bestaande uit diverse MAG-mitrailleurs vanuit het hoger gelegen deel van Mount Longdon bracht nog meer vuurkracht. Met relatief lichte verliezen bereikte A Company de oostelijke kant van Mount Longdon.

Voortzetting van de aanval door A Company

Voortzetting van de aanval door A Company

Veel Argentijnse soldaten gaven zich over of vluchtten in oostelijke richting naar Wireless Ridge. Na een gevecht van tien uur was Mount Longdon in Britse handen. Daarmee was de slag echter nog niet voorbij.

In de volgende twee dagen werden de Britten voortdurend door de Argentijnse artillerie beschoten. Nog eens vier Britse para’s sneuvelen door die beschietingen.

Daardoor liep het dodental verder op naar eenentwintig gesneuvelden en 53 gewonden. Ook de Argentijnen leden zware verliezen. Er werden 50 doden en 120 gewonden geteld. Zo’n 50 man werden krijgsgevangen gemaakt.

De veteranen van A Company vertrouwen ons in Arn-hem toe dat ze zich realiseren dat ze hun leven te dan-ken hebben aan compagniescommandant David Col-let. Als Collet de opdracht van Pike om vanuit Wing Forward de noordelijke zijde van Mount Longdon aan te vallen zou hebben uitgevoerd, dan zouden zij nog meer verliezen hebben geleden. Collet was in hun ogen als ervaren SAS-officier niet alleen tactisch sterk, maar vooral ook mentaal. Als soldaten wisten zij donders-goed dat het niet opvolgen van een opdracht van de bataljonscommandant mogelijk serieuze persoonlijke gevolgen voor hem kon hebben. Dat het daar uitein-delijk niet van gekomen is, kwam waarschijnlijk omdat de inzet van A Company in de tweede fase vanaf Fly Half naar Full Back beslissend is geweest.

DE OPMARS NAAR ARNHEM (1944)

De rol en invloed van de commandanten van 3rd Para-chute Battalion op een beslissend moment in de strijd, zowel in 1982 als tijdens Market Garden, blijkt bij een grondige vergelijking van doorslaggevend belang.

Daarbij moet gezegd dat de details van het verloop van de gevechten op 17 en 18 september 1944 voor de meeste Falkand-veteranen onbekend waren. Het is dan ook niet verwonderlijk dat de invloed van Brigadier Lathbury als commandant van 1st Parachute Brigade op de operaties van 3rd Parachute Battalion voor hen een eyeopener was.

Op de kruising bij de Koude Herberg schetsten we het verloop van de acties van B Company. Die raakte aan de westkant van Oosterbeek in gevecht met een Duitse half-track, die waarschijnlijk afkomstig was van de mobiele reserve van Kampfgruppe Krafft. In zijn recent verschenen boek Arnhem, the complete story of Operation Market Garden beschrijft William Bucking-ham de rol van Lathbury: “It’s unclear when he arrived at 3rd Parachute Battalion’s column but in the aftermath of the clash with Battalion’s Krafft mobile reserve briga-dier Lathbury’s micromanaging tendencies rapidly came to the fore. He appears to have begun virtually running the 3rd Battalion over Fitch’s head. It’s therefore likely he badgered if not simply ordered Fitch to despatch C Com-pany to the north.” Als Lieutenant Leonard Wright met zijn 9 Platoon wordt aangewezen om als spitspeloton van C Company op te treden bemoeit Lathbury zich ook met het optreden van deze compagnie. Leonard Wright: “Before I could start to brief my men about the new mission, I heard the high-pitched voice of the brigade commander… He asked what I was doing, and I replied ‘Briefing my O-group sir’. He snorted very sharply, ‘They don’t need briefing, just tell them that’s the bloody way. Get moving.’ So I did.”

EEN BESLUIT MET GEVOLGEN

Later op de avond, rond 19.30u, gaf Lathbury Fitch de opdracht halt te houden. Juist op het moment dat de nacht invalt en de Duitsers zich terugtrekken, zou je verwachten dat een parachutisteneenheid gebruik maakt van het donker en doorstoot naar de brug. Het blijkt een catastrofale maar ook onverklaarbare fout te zijn met grote gevolgen. De Britten lieten zeven kostba-re uren duisternis voorbij gaan waarin ze gebruik had-den kunnen maken van de situatie. Een dag later kwam het bataljon vast te zitten in het westen van Arnhem, op zo’n 2.500 meter van de brug. De Duitsers hadden de verdediging inmiddels op orde en hadden zich ver-

A Company neemt het gevecht over vanaf hier.

sterkt met andere eenheden. In de straatgevechten die volgden leed 3rd Parachute Battalion zoveel verliezen dat het vroeg in de morgen van dinsdag 19 september feite-lijk ophield met bestaan. “Fitch’s view is unknown because he was killed two days later, but his second in command, major Alan Bush, regarded the halt as ‘the start of the great cock up’ and was convinced that Fitch would have conti-nued moving had he been left to his own devices, probably in the wake of his C Company: ‘I felt very sorry for Colonel Fitch. If we had not had those two with us (Urquhart and Lathbury) Fitch would have probably followed C Company around that route to the north, but he could hardly move without the approval of both the divisional and brigade commanders – a hopeless situation.’ Brigade Major Tony Hibbert was more forthright in his criticism of Lathbury’s decision. Hibbert was at the Arnhem road bridge by about 20.45 and unsuccessfully urged Lathbury to despatch the 3rd Parachute Battalion down the riverside LION route during their radio exchange of 22.00. Hibbert quite rightly pointed out fifty-seven years after the event that there should have been no question of halting after such a short period on the ground and in his view, Lathbury’s refusal to move was the moment we lost the battle.”

In de gesprekken met de Falkland-veteranen werd weer eens haarfijn duidelijk dat besluiten van commandan-ten ingrijpende gevolgen kunnen hebben op het ver-loop van gevechtsacties. A Company op de Falklands had hetzelfde tragische lot kunnen ondergaan als hun voorgangers 38 jaar eerder in Arnhem. De battlefield tour op 21 september heeft hen nog meer doen inzien dat zij het geluk hadden te worden geleid door een vakkundige commandant die op het juiste moment de juiste beslissingen nam.

– Otto van Wiggen

In februari 2020 reizen de Falkland-veteranen van A Company opnieuw af naar de eilandengroep bij Argen-tinië. Dit keer om hun gevallen kameraden te eren en een plaquette te onthullen op Mount Longdon met daarop de namen van vier gesneuvelde kameraden.

Na de battlefield tour bij Schoonoord in Oosterbeek. Links: Erik Jellema. Rechts: Otto van Wiggen.

DE ROYAL ENFIELD 125 VAN HET AIRBORNE MUSEUM

BITS AND PIECES GEKOOIDE VLO

De Britse parachutisten waren tijdens de oorlog uitgerust met diverse motorfietsen.

Al jaren is in de collectie van het Airborne Museum een Britse motor aanwezig van het type Royal Enfield 125 cc LWT. Bij de laat-ste herinrichting zo’n tien jaar geleden was geen ruimte meer voor dit voertuig. Met de vernieuwing van het museum in de winter van 2019-2020 komt hierin verandering.

Het Duitse DKW (van Dampf-Kraft-Wagen) produ-ceerde in de jaren ‘20 en ‘30 naast auto’s en bromfiet-sen motoren die succesvol waren in wedstrijden en die internationaal veel aftrek vonden. In Nederland werden DKW-motoren geïmporteerd door handels-maatschappij Stokvis uit Rotterdam. Omdat het be-drijf in joodse handen was, raakte het vlak voor de oorlog de import vanuit Duitsland kwijt. Als alterna-tief liet het bedrijf in Engeland bij Royal Enfield een kopie maken van de populaire DKW RT 100 (98cc).

Dit bleek geen succes, met name omdat de Britten de technische adviezen van Stokvis negeerden.

Met het uitbreken van de oorlog kwam er dan ook een einde aan de productie, maar al ras ontstond er onder nieuw gevormde eenheden, waaronder de parachutisten, de behoefte aan een kleine, lichte motor voor snelle verplaatsingen. Royal Enfield hervatte de productie in aangepaste vorm en kwam met de Royal Enfield 125cc LWT. De machine werd bekend onder de naam ‘Flying Flea’: licht, maar sterk. En bovendien reed de motor op alle gangbare brandstoffen.

Para met een Royal Enfield (foto: Imperial War Museum, Londen).

DE VLO IN ARNHEM

In Engeland werd deze lichte motorfiets op den duur bij praktisch elk legeronderdeel en ook bij de lucht-macht gebruikt. Door het geringe gewicht was de ma-chine behoorlijk terreinwaardig en zeer geschikt voor gebruik door luchtlandingstroepen.

Hoeveel Royal Enfields in september 1944 bij Arn-hem zijn ingezet is niet bekend. Gemiddeld had een luchtlandingsbataljon in 1944 de beschikking over 43 lichte motorfietsen; een parachutistenbataljon had er vermoedelijk wat minder. Aangenomen wordt dat er enkele honderden dienst hebben gedaan tijdens de slag. De meeste werden gebruikt door ‘despatch ri-ders’ die berichten tussen eenheden overbrachten.

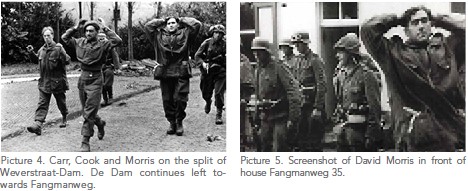

In de Arnhemse verslagen worden de Enfields slechts enkele keren genoemd. Wel zijn er enkele foto’s waar-op dit type motorfiets staat afgebeeld, zoals die van Duitse krijgsgevangenen die op 17 september worden afgevoerd langs de Parallelweg in Wolfheze. Links is, achter de loop van een 17-ponder-kanon, nog net een klein deel van een Enfield zichtbaar. Een Duitse foto van 19 september toont Britse krijgsgevangenen op de Utrechtseweg bij het Gemeentemuseum in Arnhem. Zij worden begeleid door een Duitser die een Flying Flea voortduwt met de hand.

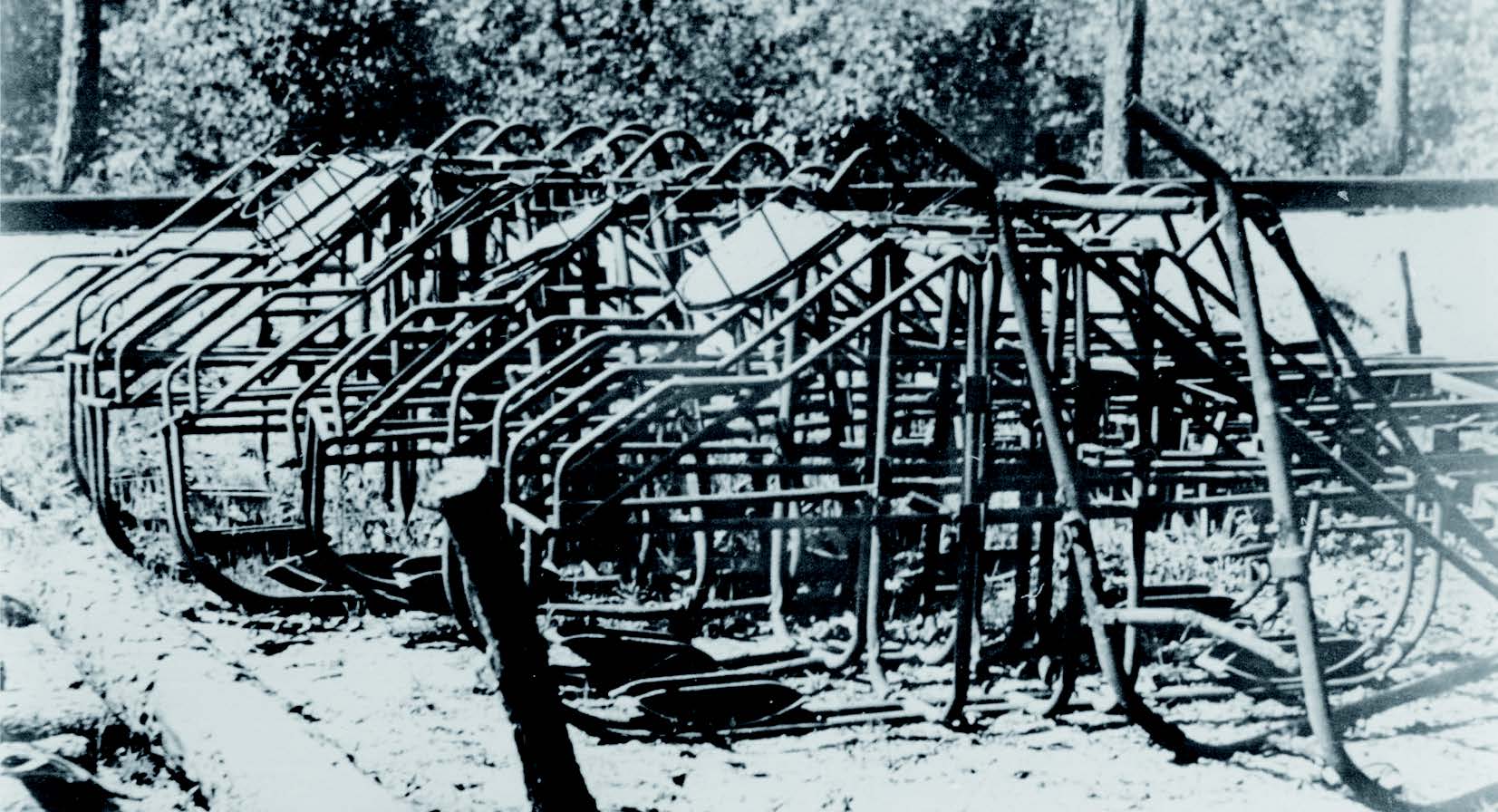

Royal Enfield ‘Flying Flea’-motorfietsen werden gedropt. Bij het opruimen van de landingsterreinen bij Wolf-heze, na de bevrijding in 1945, werden deze frames samen met allerlei onderdelen van gliders, containers en ander achtergelaten materiaal opgeslagen langs de Wolfhezerweg. Achter de frames is het lage dijkje van de spoorlijn naar het vliegveld Deelen zichtbaar. De fotograaf had kennelijk weinig verstand van dit soort materiaal. Hij noteerde bij deze foto: “Achtergelaten stoelen van zweefvliegtuigen” (foto: via Robert Voskuil).

AFPLAKTAPE

Veel oudere bewoners van Oosterbeek en omgeving herinnerden zich dat er ‘Flying Flea’-motorfietsen wa-ren achtergelaten bij de landingszones. Ze waren niet beschadigd, maar functioneerden desondanks niet.

De oorzaak daarvan was vaak een simpele: vóór de vlucht naar Nederland werd het ontluchtingsgaatje in de benzinedop afgeplakt om te voorkomen dat tijdens de vlucht benzine zou wegvloeien, wat tot brand kon leiden. Als de motorfietsen na de landing haastig wa-ren uitgeladen, reden de berijders vaak weg zonder de afplaktape van de benzinedop te verwijderen. Daar-door kreeg de carburateur al snel geen benzine meer.

Dichter bij Arnhem werden Enfields gevonden die moeilijkheden hadden met de ontsteking. Een veel voorkomend euvel, dat wel lastig was, maar gemakkelijk kon worden verholpen.

Royal Enfield met dropkooi in de Glider Collection in Wofheze (foto: Leo van Midden). De ijzeren kooi waarin de motorfietsen konden worden gedropt, bestond uit een stelsel van buizen en werd ook door de Royal Enfieldfabriek gemaakt. Dit zogenaamde ‘crash proof’-frame bleek in de praktijk echter niet altijd crash proof.

Ondanks het feit dat deze lichte motorfietsen vóór, tijdens en na de oorlog verkocht en bijna onveranderd gebruikt zijn, is het toch opmerkelijk dat er nog zo weinig zijn. In het Imperial War Museum in Duxford (Engeland) is een complete Royal Enfield in een bui-zenframe met parachute tentoongesteld.

RESTAURATIE

De motor die het Airborne Museum bezit is ooit ge-deeltelijk gerestaureerd, maar er ontbreekt nog het nodige aan dit exemplaar. Met financiële steun van de VVAM wordt de Flying Flea nu weer in de oor-spronkelijke staat gebracht. Missende en niet juiste onderdelen zullen worden aangeschaft, verkeerd ge-monteerde delen worden opnieuw geplaatst of ver-vangen. Zowel de motor als de dropkooi worden op-nieuw geschilderd. Voor de kleur van de motor zijn twee mogelijkheden: bruin, de door de Britten toege-paste kleur uit het begin van de oorlog, of groen, de latere kleur die voor alle geallieerde voertuigen werd gebruikt. Uit bodemvondsten is gebleken dat beide kleuren tijden de slag zijn gebruikt. De nummering wordt weer aangepast naar 1944.

De Flying Flea die in 2007 werd opgegraven.

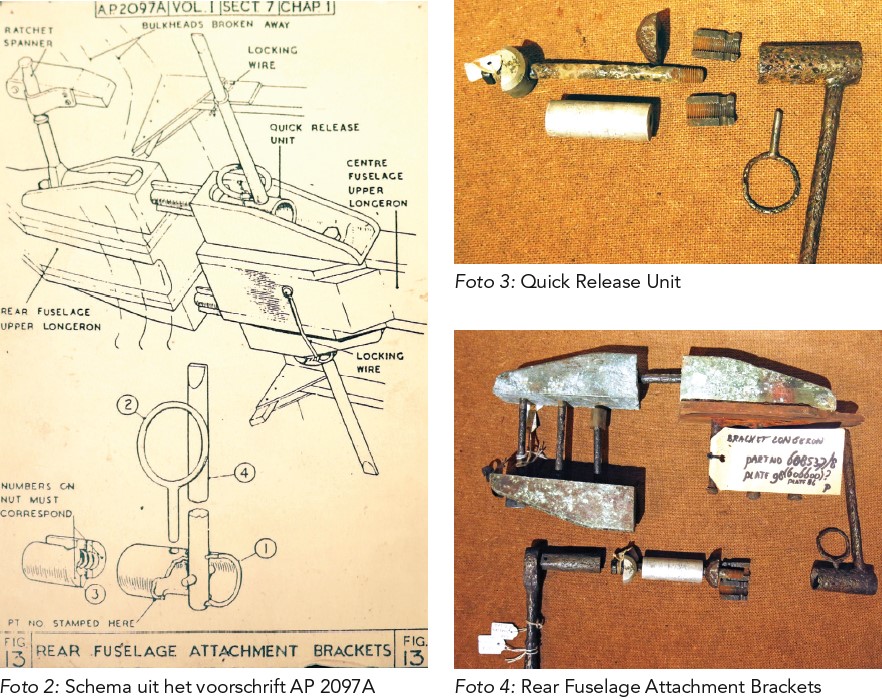

De bewaard gebleven voorschriften uit de jaren ‘40, gave uitvoeringen en bodemvondsten dienen als basis voor het restauratieplan. In 2007 werd in de omge-ving van de Johannahoeve bij Oosterbeek een Flying Flea opgegraven die in zeer slechte staat bleek te ver-keren en bovendien incompleet was: het motorblok was vergaan, de wielen en carburateur waren niet meer aanwezig. Wel is het frame bruikbaar als voor-beeld van een Flying Flea die is gebruikt tijdens de slag om Arnhem.

Tijdens de bouwwerkzaamheden in de Betuwse wijk De Schuytgraaf, op de voormalige Poolse dropzone bij Driel, zijn zo’n twintig jaar geleden delen van drop-kooien opgegraven. Uit de veelheid van losse buisdelen is later een complete dropkooi samengesteld.

De gerestaureerde Royal Enfield en ‘Poolse’ kooi zullen vanaf 2020 onderdeel gaan vormen van de per-manente tentoonstelling in het herboren Airborne Museum.

– Wybo Boersma

Samenstelling van de ‘Poolse’ dropkooi.

Bronnen: • M. Veldhuizen, Ministory 20; De motorfiets “Flying Flea” bij de Slag om Arnhem (bijlage bij VVAM-Nieuwsbrief 31). • Het motorrijwiel 12/1944. • De Flying Flea ofwel Vliegende Luis door M. Veldhuizen in: Terugblik, maandblad van de Documentatiegroep ’40-‘45. • Brits voorschrift 18426 (1 (433) pag. 603, Gegevens motorvoertuigen.

DE VERBORGEN MARKET GARDEN-SCHATTEN VAN ERFGOEDCENTRUM ROZET

ACHTERGROND STUKKEN DIE NIEMAND MEER KENT, BOEKEN WAARAAN NIEMAND MEER DENKT

Wie het souterrain van Rozet in Arnhem betreedt, daalt af in het Gelderse verleden. Een kleine wereld van indirect licht, gedempte geluiden en objecten die niet zouden misstaan in het Rijksmuseum. Een belangrijk deel van de collectie bestaat uit documentatie gere-lateerd aan de slag om Arnhem en aan de strijd in de maanden erna. Zomaar een donder-dagnamiddag tussen de boeken en archiefstukken van Erfgoedcentrum Rozet.