Ministory 068 – A DUTCH COMMANDO

MINISTORY 68

A DUTCH COMMANDO

By commando corporal Tom Italiaander

Six months before his death (on 28 March 2000), Tom Italiaander recorded on paper his personal experiences of the Battle of Arnhem at the request of the Airborne Museum ‘Hartenstein’. As one of the 12 Dutch commandos seconded to the lst British Airborne Division he was attached to the lst Airlanding Squadron, Reconnaissance Corps (Recce Sqn). An interview with Italiaander was published in the book ‘Zwevend naar de dood’ by Th. Peelen and A.L.J. van Vliet (1977), which runs more or less parallel with this report. The article lias been reproduced in its original state asfar as possible and, where necessary, has been edited and provided with footnotes by Wybo Boersma.

When, at the end of 1937 1 left IJmuiden on board the ‘Caribia’ (of the German Hapag line) bound for Latin America, where I was to carry out geo-physical research as part of a multi-national firm, I could never have imagined that some seven years later, on 17 September 1944 to be precise, I would be returning to the Netherlands by air in a Horsa glider from an airfield in Lincolnshire, England.

How it began

Towards the end of 1940, while working in the Ecuadorian interior and despite being eligible for military service, 1 was approached by our ambassador in Bogota with a view to my volunteering for the Dutch Legion, which al that time was quartered in Canada. From there it would be leaving for England. Although this meant resigning from the multi-national firm I responded to the call, and at the end of June 1941 joined up with the Irene Brigade at their barracks near Wolverhampton. The general atmosphere there did not match what 1 had envisaged and for which I had sacrificed so much, so, after a few unsuccessful attempts, I managed to obtain a transfer to a British commando unit.

After a period of pretty intensive additional training at Achnacarry in Scotland, No. 2 (Dutch) Troop was formed in August 1942 as part of No. 10 (Inter Allied) Commando. In mid-December 1943 No. 2 (Dutch) Troop was transferred to India, from where it was to take part in the Sumatra landings under the command of Lord Louis Mountbatten. However, the attack on the then Dutch East Indies was cancelled when the necessary landing craft, which were already in the Bitter Lakes in Egypt, were recalled for use in the Normandy landings.

No. 2 (Dutch) Troop then received permission to return to the European theatre of operations, just in time for deployment in operation Market. However, this would not be in a troop formation but as Signals personnel spread throughout the combat units involved, namely the lst British Airborne and the 82nd and lOlst U.S. Airborne Divisions. As one of twelve Dutchmen seconded to the British Division, I was attached to the recce unit.1).

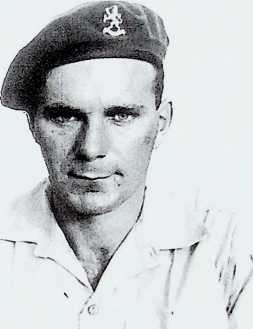

Tom Italiaander as ‘corporal-commando’ in the uniform of No. 2 (Dutch) Troop No. 10 (Inter Allied) Commando, 1944. He is seen here in India, shortly before leaving for Europe.

(Italiaander collection)

Operation Market Garden

A long line of Stirling bombers, each with a Horsa glider attached to it by a tow rope as big round as your fist, was drawn up on the runway when we boarded our allotted machine. 2)

By ‘we’ I mean the two pilots and my two British comrades-in-arms. We made our way to the glider’s tail section where we sat down on the bench seat that was fitted with safety beits. In addition the glider carried two jeeps, heavily laden with arms, ammunition and petrol supplies.

The mug of tea (laced with about 50% rum) that we were offered just before take-off only marginally suppressed the mixed feelings we had about what lay ahead. One by one the dozens of Horsas were towed into the air, where they then formed up and headed for Arnhem.

Although there had been talk of some enemy activity we experienced little trouble thanks to our escorting fighters, who flashed about us continuously. It was an emotional moment when I caught sight of the sun reflected in the waters of inundated Walcheren.

At about 2 pm we arrived over the landing zone at Wolfheze and the pilots cast off from the Stirling. Th is brought an im media te end to the noise caused by the slipstream and we descended in almost dead silence. The pilots managed to get down with only a very modest bump, but not all Glider Pilots were so successful. The aircraft that came down behind us failed to land in time and left ils wings behind among the trees fringing the landing zone before coming to a halt. A Hamilcar glider, used for transporting heavier equipment, braked too hard on landing on the soft ground and turned over onto its back, with disastrous consequences for the pilots who were seated in a cockpit above the load. 3).

Af ter we had unloaded the Horsa and the unit had rendezvoused, the Recce Sqn made an unsuccessful attempt to advance towards Arnhem along a track north of the railway line. German snipers caused the first losses here. I too came under directed German

fire for the first time, something, which caused momentary panic.

Self confidence soon returned when the lessons learned during the thorough commando training were applied. Efforts to eliminate this disruptive element and to recover the victims failed. The Jatter could only be carried out after darkness feil. 4).

Sunday night was spent between the jeeps, close to the burning Institute for the Blind in Wolfheze. Next morning, following the temporary field burial of the dead, the advance was resumed, now along the main road (Wolfhezerweg-Utrechtseweg). This proceeded painfully slowly and little progress was made due to the increased German pressure and the many skirmishes. The second night was spent in the vicinity of a deserted hotel (the Bilderberg?). This again called for great improvisation because we were slill without our kit, which included our sleeping bags. This equipment should have come with the second lift, and although this lift had arrived on Monday afternoon we never saw any sign of our stuff.

On Tuesday the 19th the squadron Consolidated in Oosterbeek in the area of the Hartens tein Hotel. 5). The military situation forced us to take up defensive positions and, despite a number of breakouts attempts, our headquarters remained here until Monday 25 September.

Every day two-man patrols were sent out to the

Monday morning, 18 September ‘1944. On Duitsekampweg in Wolfheze, two residents, Mrs Tjooiik and Maart je van der

Poel, have brought out the national tricolour and share their joy with Dutch commandos Private Jef van der Meer and Corporal Tom Italiaander (right). The photo was taken by Sergeant Dennis Smith of the Army Film and Photographic Unit.

The information comes from the book ‘Blik Omhoog, Volume II by Cor Janse.

(Courtesy Imperial War Museum, London, BLl 1153)

forward positions dotted along the perimeter. These posts began to suffer more and more from the attentions of an increasingly brash enemy, often supported by M 88 self-propelled guns.

Most posts possessed radio transmitters whose working left a lot to be desired, probably due to the wooded and built-up surroundings. The patrols also had the job of providing the men at the outposts with alternative codes for their radio communication.

Although the positions were not far from the Hartenstein Hotel as the crow flies, these operations became increasingly tricky and a sort of tightrope walk. Contributory factors here were the metal studded dreadnoughts’ with which the Tommies were shod. Silent movement was therefore impossible, and the noise they created quickly attracted the attention of snipers. The commandos were equipped with SV boots which had heavily- ribbed rubber soles.

One of the patrols I took part in was to a position located in a deserted bakery in Paul Krugerstraat. 7) An outpost manned by two British soldiers had been set up there. They had made the rear of the house very comfortable for themselves and had mounted a Bren gun on a raised table. From here they had a good field of fire to the north through a half bulls-eye window from which the glass had been removed. The shop at the front was very neat and tidy, with a counter at the rear and a dozen or so shiny, cream painted, pot-bellied tins in racks. Their former contents were indicated on the front in large gold letters in a beautiful, copperplate script. Not surprisingly, further inspection revealed not a single scrap of these former contents.

At that moment we couldn’t have imagined that we would nol see our two comrades again. It must have been Wednesday or Thursday when the post didn’t answer its radio call. Although we hoped it was simply a transmitter failure we feared the worst, especially since a fair amount of enemy activity had been observed in that area recently. The patrol that went out as darkness feil found a ruin, but no sign of life.

We had dug in at the edge of an open field with a wood opposite us about hundred melres away. It was not long before the enemy had settled in there and their aimed fire seriously restricted our freedom of movement. However, when the Germans brought up a mortar, our position became untenable due to shrapnel caused by bombs exploding in nearby trees. That night we worked like beavers preparing new, less vulnerable positions and we were able to hold these until Monday 25 September.

The fetching of supplies and contact with headquarters took place during the hours of darkness when we considered ourselves relatively safe. We could then leave our trenches and stretch our legs for a while, and the abandoned positions came in handy as a latrine. But, because of the continuing threat of a breakthrough, one of us had to

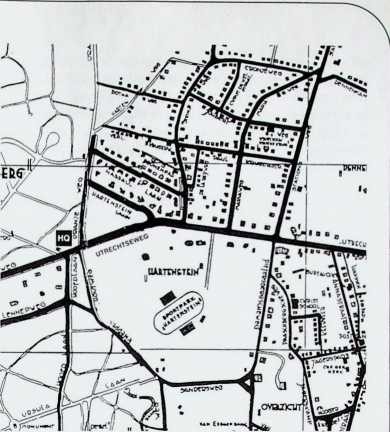

Part of o Street map of Oosterbeek daling from around 1939 showing, among other things, Isl Airlanding Squadron Reconnaissance Corps HQ during the period 19-25 September 1944.

(Municipal Archive Renkum collection)

be on the alert at all times, no easy task considering we were in a constant stupor through lack of sleep.

It would have been Friday or Saturday that our morale was at a low point, partly due to the fact that a number of Dakotas had been lost. Their courageous crews had been attempting to parachute much- needed supplies in to us, but alas, most fell outside of the perimeter and into enemy hands. And of course the non-arrival of 2nd Army did nothing to lighten the mood.

A glance over the parapet was met with a salvo of aimed German fire. Normally, it is difficult to pinpoint exactly where fire is coming from, but this time I spotted a flash at the edge of the woods opposite. It was a great boost when I emptied a magazine from my Tommy gun into the offending spot and was ‘rewarded’ with a scream.

In the evening, returning with rations and ammunition collected from battle-damaged jeeps parked near the Hartenstein tennis courts, 1 was surprised by the characteristic ‘thump’ of a mortar being fired. Without a second’s thought I dived into a nearby deserted trench. Too late though. As if predestined the bomb landed in the trench with a thud, but failed to explode thanks to the loose soil. It was some time before I was over the fright and before the scattered slips of paper had floated back to earth. 8)

It had gradually dawned on us that this operation now had to be considered a failure, and so it came as a relief when, at 9 pm in the evening of Monday the 25th, we received the order to withdraw. The route was clearly marked with white tape by the Engineers. Holding on to one another in the dark we set off in a southerly direction towards the Rhine, the last obstacle on our way to safer climes. Although it was drizzling and we made very little noise, I nevertheless got the impression that the Germans had got wind of the evacuation because the patrols protecting our flanks were in contact with the enemy on several occasions. When we reached the flood plains we were greeted with mortar attacks. Although frightening, the haphazardly fired shells had little effect on landing because of the sodden ground. More casualties were caused by the explosive shells fired by Oerlikons from the opposite bank downstream.9)

It is terrifying to see tracers coming straight at you; something you never forget.

In spite of these dangers the majority of the squadron managed to reach the south bank thanks to the Engineers from the ground forces. These men ran a continuous shuttle service in their outboard-driven storm boats with a total disregard for death. It also has to be said that the success of the evacuation would have been impossible without the fantastic and uninterrupted artillery barrage from the south. Undoubtedly, this ‘umbrella’ contributed to the fact that the Germans did not overrun the boarding points. A feat of arms that has still not been given its much-deserved attention. I heard later that 1,400 gun barrels were ‘worn out’ during this barrage.

We were met on the south bank and moved on to Nijmegen via a first aid post set up in a farm. The memory of that trip, sitting on the bonnet of a packed jeep, in a wet uniform, slipping and sliding on a virtually impassable road in the rain, has remained with me for a long time.

We wanted to get back to England as quickly as possible, so it came as a disappointment when the three lorries earmarked for the Recce Sqn, or at least what was left of it, for transportation on Wednesday were allotted to the Glider Pilot Regiment at the last min ute.

Next day, some ten kilometres or so outside Nijmegen on the road to Leuven, where we were to spend the night in a convent, we passed the three burnt-out army lorries. In the Belgian town we heard that the Germans had broken through the narrow corridor the previous day, with disastrous consequences for the pilots’ transport which was on the road at the time.

On Friday we flew back to the United Kingdom in Dakotas from an airfield just outside Leuven. Fiere, at the base near Lincoln, we were given a tremendous reception with fanfare, speeches, snacks and suchlike, as if our mission had been a total success.]1)

The majority of the survivors from No. 2 (Dutch) Troop, No. 10 (Inter Allied) Commando took part in the landings on Walcheren in November 1944.

NOTES

1) For the other secondments see the publications Korps Commandotroepen 1942-1982′ published by the Commando Foundation in 1982, and ‘Het Korps Commandotroepen 1942- 1997’ (SDU Publishers 1997).

2) Italiaander left from Tarrant Rushton airfield on 17 September 1944 (incidentally in Dorsetshire, roughly 200 miles from Lincoln). The Horsa was towed by a Halifax aircraft. See page 97 of the book which appeared this year, ‘Tugs and Gliders to Arnhem’, written and published by Arie-Jan van Hees.

3′) The Reconnaissance Squadron landed on landing zone ‘Z’. The Hamilcar glider carried a 17-pounder anti-tank gun and a Morris Commercial C 8 towing vehicle.

4) Italiaander was not mentioned in John Fairly’s description of the Recce Sqn’s advance in Iris book. ‘Remember Arnhem” (see pages 41-51). He was probably attached to headquarters.

5) Near the Oranjeweg-Utrechtseweg Crossing, diagonally opposite the Hartenstein Hotel.

6) Self-propelled guns. The type of vehicle referred to is probably the Panzerselbstfahrlafette Ifiir 7,62 cm Pak 36 (r) (Sd.Kfz. 132). ‘Pak’ standsfor Panzerabwehrkanone = anti-tank gun. These belonged to SS-Panzerjager Ausbildungsabteilung 2 that was attached to Kampfgruppe Von Tettau (Westgruppe).

7) Paul Krugerstraat 23 (north west corner with Mariaweg), the Cntm family bakery.

8) The author probably meant to say: ‘Before 1 had sorted everylhing out’.

9) In the darkness it wotdd have been doubtful if the allies could have made out precisely where the enemy fire was coming from. If the type of gun could be identified is also questionable. The author was probably confusing the covcring fire from their own ground troops in the Betuwe with German activities from such places as the Weslerbouwing.

10) Unforlunalely, more Information on this incident is not (yet) known.

11) On 28 September the squadron left for Leuven. Next day they arrived in Lincolnshire.

Not only was the failure of the operation a tremendous disappointment, so too was the failure to meet up again with my parents, something which I had looked forward to with longing for so many years. This reunion would eventually take place on 10 May 1945.

Plaats een Reactie

Vraag of reactie?Laat hier uw reactie achter.