Ministory 060 – THEY ALSO CALLED THEMSELVES ‘FREIKORPSKAMPFER’

MINISTORY 60

THEY ALSO CALLED THEMSELVES ‘FREIKORPSKAMPFER’

by Peter Berends

Introduction

After landing near Arnhem on Sunday 17 September 1944, the Ist British Airborne Division clashed with, among others, the 2nd SS Panzer Corps commanded by General Wilhelm Bittrich. This corps consisted ot’ the 9th SS Panzer Division ‘Hohenstaufen’ and the lOth SS Panzer Division ‘Frundsberg’. These two units had suffered heavy losses since June ’44, both in the fighting in Normandy and thereafter during their withdrawal to the Netherlands, but in spite of that they still possessed sufficiënt armour to offer stern opposition to the allies.

Bittrich sent Lieutenant Colonel Walter Harzer’s Hohenstaufen Division to the battle area near Oosterbeek and Wolfheze with orders to prevent the British from capturing the Arnhem road bridge, and then to defeat them.

The Frundsberg Division under Major General Heinz

Harmel was given the Betuwe as its area of opera tions. lts task was to prevent Allied ground forces linking up with the airborne troops in the Gelderland Capital via the bridge over the Waal at Nijmegen. Part of the Frundsberg Division was also deployed in central Arnhem on that Sunday evening in order to recapture the northern approach to the Rhine bridge, which the British had managed to occupy. This involved the ‘Kampfgruppe Brinkmann’ and a few loose units from that division, to which Wilhelm Balbach also belonged.

Wilhelm Balbach

SS soldiers fleeing from France were still arriving in the Arnhem area up to a few days before the 17th of September. Among these was 19 year old Wilhelm

A German Schützenpanzerwagen (type Sd.Kfz. 250/1) from the SS-Pniizer-Aufklilrungsabteilung 10 (reconnnissnnce unit), 10 SS-Panzer-Division ‘Frundsberg’, on the approach to the Rhine bridge after its recapture on 21 September 1944. On the left is the destroyed bunker next to the bridge and in the background, Arnhem in the mist.

(Photo: Bundesarchiv, Koblenz)

Balbach, ‘Sturmmann’ (Private 1 st Class or Corporal) with 8 Company, 2 Battalion, 22 SS Panzer Regiment of the lOth SS Panzer Division ‘Frundsberg’.

Wounded in the upper arm by shrapnel during the fighting in Normandy, Balbach avoided the German catastrophe there, having been despatched to Germany in transport for the injured.

He reached Siegen in Western Germany by way of Paris and a detour via Darmstad! and Brussels. Although by mid-September 1944 his wounds were still nol entirely healed, the German higher-ups were of the opinion that he and other wounded servicemen in the group were fit enough to return to duty somewhere or other. And so it was that he and a few hundred others were sent to the Netherlands.

Arnhem

On Saturday 16 September the group drove through Arnhem. A peaceful city of 100,000 inhabitants, so says Balbach, situated far behind the front lino.

At that moment he had no idea that the area would present a much more violent face within a couple of days.

Outside of Arnhem (probably near Zutphen), the group was split up into specific units.

It appeared to Balbach that the lOth SS Panzer Division had been completely reformed.

No-one knew which unit he belonged to with any certainty, and Balbach knew none of the people. Here in the Netherlands all those who had managed to escape from Normandy were put in units again

On Sunday 17 September, Wilhelm Balbach’s group was warned of the allied landings and sent off in the direction of Arnhem. There were hardly any vehicles available and up to now no clear units, platoons or companies had been formed. The men feit like a ‘Kampfhaufen’ (hastily thrown-togelher group) of randomly assembled ‘alle Hasen’ (battle-hardened veterans), who were however only 18 to 20 years old. Despi te the differences in rank, a sort of spontaneous chain of command developed in which the man with the most mentally dominant personality began issuing orders quite naturally and, by his actions, showed clearly which function he had actually assumed within the group.

Balbach and about 10 others were lucky enough to end up on a ‘Schützenpanzerwagen’ (SPW).

Going into battle in an armoured half-track such as this was a totally new experience for Balbach. When it was dark the group plus some other soldiers sought shelter in a few farms on the outskirts of a village (probably along the Veluwezoom).

Even by the morning of 18 September they still had no inkling of how the battle was progressing in the Gelderland Capital. The men tried to obtain Information and began preparing themselves for the worst. But there were no clear orders for what they had to do in Arnhem, and none arrived.

11 appeared as if the local Dutch population was just going about its normal daily routines as if nothing in

particular was happening a little way off. To Balbach and his comrades, used to heavy front-line action, it seemed that total peace reigned around and about them.

One of the SPW crew had managed to get hold of a box of cigars which, to his amazement, hardly anyone wanted. Then he just lil one up himself with the words ‘This could well be my last’.

The cigar band bore the words ‘Willem van Oranje (William of Orange).

Shortly af ter the troop had been told to head for Arnhem the order was rescinded, and fresh orders sent them to another village to the east of Velp where they were left to wait at the side of the road for hours on end. To pass the time they sat on the kerb watching the many fresh young Dutch girls cycling or walking by.

It was not until the afternoon that they received firm orders to depart. They entered Arnhem via Velperweg and Steenstraat. There they were told that they should now proceed more carefully: the British were in the town. They drove the SPW past the Café Rotonde (the bowed ‘bay window’ part of the Musis Sacrum on Velperplein, the then ‘Wehrmachtsheim’ (the recreational quarters of the German Army), and reached Roggestraat, the start of the actual centre of Arnhem.

Here they left the armoured vehicle and began advancing cautiously on foot, hugging the walls of the buildings.

Turning left they entered Koningstraat and continued on towards the bridge via Kerkstraat. There were no civilians to be seen, and where in fact were the British? Had they fallen into the trap? To proleet themselves from attack from the houses they forced their way into the buildings and drove the inhabitants onto the streets. They had to do this because the houses in the city centre were all three or four storeys high, impossible to search with just a handful of men.

Once outside the civilians were interrogated by the German soldiers, who asked if there were any British in the houses.

The answer was always in the negative.

Nobody was concealing any British in their house, in fact no-one had even seen any sign of the allies. Despite these assurances Balbach and his mates were convinced that there were many British still hiding in the houses, but of course they were wisely keeping quiet.

This time-consuming work of driving the civilians from their homes and interrogating them meant that they had not advanced very far in the direction of the bridge. By evening they had only got as far as the Cinema Palace picture house in Bakkerstraat.

The doors to the cinema were set well back from the streel with a sort of forecourt in front, a seemingly ideal place to station the SPW.

The driver reversed into the en trance, leaving just the ‘snout’ of the armoured vehicle protruding beyond the fagade of the building.

In this way they were well protected against sudden attack and had escape routes to the left and right in the event of an emergency.

From their strongpoint in the Cinema Palace Balbach and comrades began to reconnoitre the closest by parts of the inner city, leaving a few sentries at the cinema. During their resumed advance towards the bridge they entered the Twentsche Bank, to find staff still present (these people had probably remained on the premises in order to save what they could), The bank building formed part of the Southern limit of the central built-up area and survived the battle virtually undamaged.

Balbach’s men were thirsty and asked the bank manager for water. Because the water supply no longer appeared to be working properly, the Dutchman took Balbach and one of his comrades through a maze of corridors to the cellar, where water was still available. ‘Although there were two of us’ says Balbach, ‘we were uneasy. This came from the fact that we were being asked to carry out a task here in Arnhem for which we were not really trained, and had not even experienced in our fighling in Russia and Normandy. However, il seems that we carried out much of what we did intuitively and cor- rectly during the battle in the inner city.

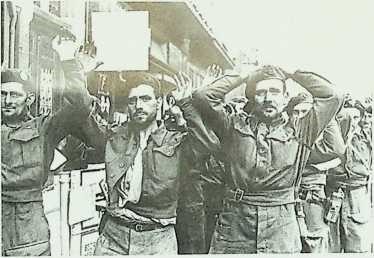

British parachutists captured near the Arnhem rond bridge, phologrnphed in the inner cit\j(?), September 1944.

(Photo: Bundesarchiv, Koblenz)

When we returned from the cellar to the spacious office we feit completely at ease again in sight of the Dutch girls there’.

In the night of 18/19 September Balbach and the rest of the SPW crew made themselves as comfortable as they could in the city centre, with sentries posted around the half-track for safety. In the middle of the night one of the crew suddenly began swearing that he had had enough. ‘You lot can gel lost. I must be mad lying here in your stupid, uncomfortable SPW, my bones getting more painful by the minute, while all around us are houses with nice soft beds. I’m off to find a bed’. The uproar woke Balbach who tned to talk the incensed man round, bul he was adamant, leapt from the half-track and made an attempt to enter the nearest house.

Almost immediately following this risky initiative hand grenades began exploding close to the SPW, and in a trice the men’s situation had changed to one of real war. Now everyone jumped out of the vehicle and began firing in all directions with tracer ammunition. For a moment everything was more or less brightly lit, but suddenly it became pitch black again and not much more could be done. In the meantime they had to keep a good lookout in case they were treated to another shower of hand grenades from the houses all around them.

When it was light (19 September), Balbach and his comrades broke into the house from which the attack had come during the night. The opposition was moderate and they were soon back outside with 16 British prisoners.

For the rest of the day and the next (the 20th), Balbach’s small group were heavily engaged in house-clearing in central Arnhem.

The tactics they developed for this house-to-house fighting was as follows. When forcing an entry the first man provided cover with a rifle or carbine. The second man smashed or kicked the door down and the third dashed inside. In this way the houses were systematically combed for the enemy.

The best weapon for this work seemed to be a piece of equipment intended for an entirely different use, namely a flare pistol firing cartridges fitted with a whistling or si ren device.

A cartridge would be fired into the house and would then ricochet from wall to wall, criss-crossing the rooms and emitting a piercing scream. This devilish racket demoralised the already dog-tired British soldiers who, generally, quickly surrendered as a consequence.

The German soldiers were surprised to find that the British were carrying new paper money (including Dutch banknotes hearing the portrait of Queen Wilhelmina). The soldiers made many jokes about this ‘occupation money’ as it was called.

The British also had beauliful white handkerchiefs which, when opened up, appeared to have maps printed on them. Balbach kept one of these until the end of the war. Some of the enemy’s uniform buttons even contained compasses! But by far the best of the British equipment, according to Balbach and his mates, were the large, bright yellow silk neckerchiefs, which were subsequently used as recognition signs by this small, randomly assembled group of men from the Frundsberg Division.

These fighters who ‘waged a solo war’ also referred to themselves as ‘Freikorpskampfer’ (Independent warriors).

As was the case with their opponents, the German troops received little in the way of food during the fighling. However, in the cellars of the houses Balbach and his men found dozens of glass jars of preserved fruit, which stilled their hunger and quenched their thirst at the same time.

What they really missed was clean underwear.

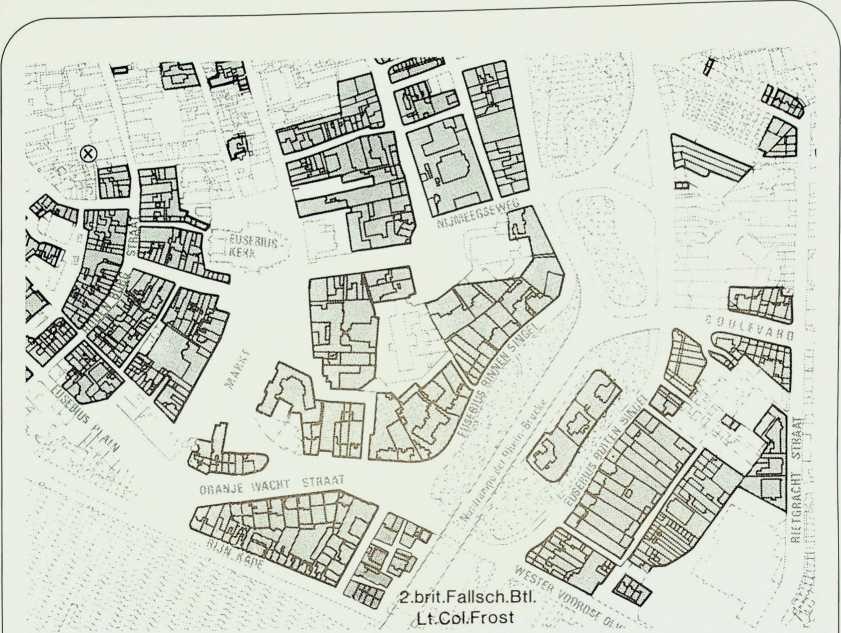

The Cinema Palace is markeet (X) on this ‘1945 streel map of Arnhem; the shaded portions indicate destroyed buildings.

(Map: Berends collection)

But by chance even this problem was abundantly resolved. A Rhine barge moored at the quay appeared to be crammed fu 11 of fresh underwear. Although this was one problem out of the way the men just could not get rid of the lice ‘acquired’ at the front because, in spile of the clothing being so clean, the ‘little critters’ refused to be driven out.

During the hours of darkness Balbach was occasionally sent to report to the ‘Sonnenstuhl’ command post, a task in which everyone look his turn and which involved Crossing part of the city. The post was in one of the houses on the eastern side of the Velperbuitensingel, opposite the side of the Musis Sacrum. To reach the post Balbach had to go through Koningstraat, a journey that was in fact much more dangerous than he had ever realised it could be! How simp Ie it wou ld have been for the British, concealed unbeknown to him in the buildings, to end his life. In those empty, dark streets his death would have gone unnoticed.

According to Balbach the actions by the allied air forces and artillery al Arnhem were insignificant compared to that experienced in the fighting in Normandy. And in the city itself, despi te their military superiority, the enemy could not attack the Germans non-stop, day and night.

Here they were forced to fight their opponents on even terms (hand to hand).

Even the reca plu ring of the bridge in Arnhem by the Germans on 21 September 1944 brought little respite to Balbach and his comrades.

They were quickly transferred to the Betuwe to oppose the northerly advance by the British 30 Corps via the Waal bridge in Nijmegen.

Their new battlefields were at Eist and Haalderen.

Here they became acquainted with the flat and marshy Betuwe meadows where, because of the high water table, good cover was very difficult to find.

What befell them there is outside the scope of this story.

The above originates from ‘Die Hellebarde’, Nachrichten der Kameradschaftsvereinigung, Suchdienst Frundsberg (1991) [the Frundsberg veterans’ association magazine].

Wilhelm Balbach’s experiences will appear in the manuscript ‘De 9de SS-Pantserdivisie Hohenstaufen en andere Duitse formaties in de Slag om Arnhem, september – oktober 1944’ (The 9th SS Panzer Division Hohenstaufen and other German formations during the Battle of Arnhem, September – October 1944), which is to be published by Peter Berends in the (near) future.

Plaats een Reactie

Vraag of reactie?Laat hier uw reactie achter.